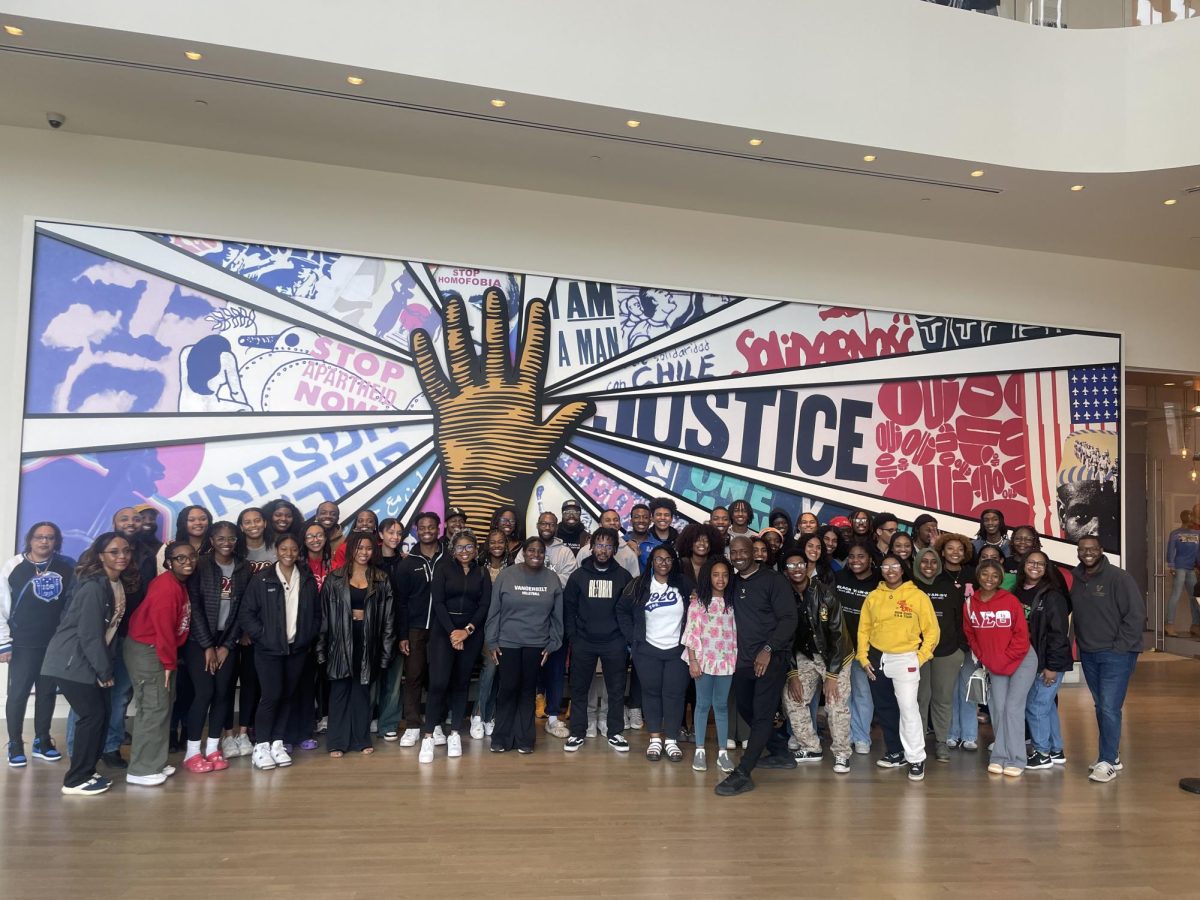

In mid-January, 48 received an invitation to attend the 2023 Black History Immersion Excursion. Last weekend, these students had a transformative experience in Alabama. Students and faculty traveled to Montgomery and Selma, where they visited a series of historical destinations telling the history of Black Americans over the last 500 years.

Carefully planned and led by Black Cultural Center Director Dr. Rosevelt Noble, this was the third excursion that the BCC has hosted and the first since February 2020.

In Montgomery, Alabama’s capital, we first visited the Freedom Rides Museum. The museum was built at what was previously the Montgomery Greyhound Bus Station, the site of a violent attack on participants on the 1961 Freedom Ride. The “Freedom Riders,” most of whom were Nashville college students, were testing the true effects of the 1960 Supreme Court decision that declared segregation in transportation facilities unconstitutional. We then walked to the Rosa Parks Museum, where we learned not only about the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott but also about Rosa Parks’ pivotal role in it.

The following morning, we started with my favorite museum of the trip — the Legacy Museum. It displays an in-depth history of slavery and racism in America. The museum’s careful curation of intense and beautiful exhibits teaches visitors about the enslavement of African-Americans, racial lynchings and segregation, as well as modern-day racial bias and mass incarceration. The Legacy Museum was especially packed with information — afterward, trip participants collectively decided that even four hours wouldn’t be enough to thoroughly understand all the information and history that was covered at the site.

This roadmap of Black history didn’t skimp on any details nor did it seek to obscure the raw truth therein. One exhibit featured moving pictures — holograms, if you will — of slaves, with their projections displayed in small wooden cells. One hologram of a woman was singing gospel songs. I don’t know exactly why, but that was what broke me – I began to cry. I wasn’t the only student who felt strong emotions after that stop — even Vanderbilt staff struggled with some of the heavy material. We weren’t allowed to photograph this site, out of respect.

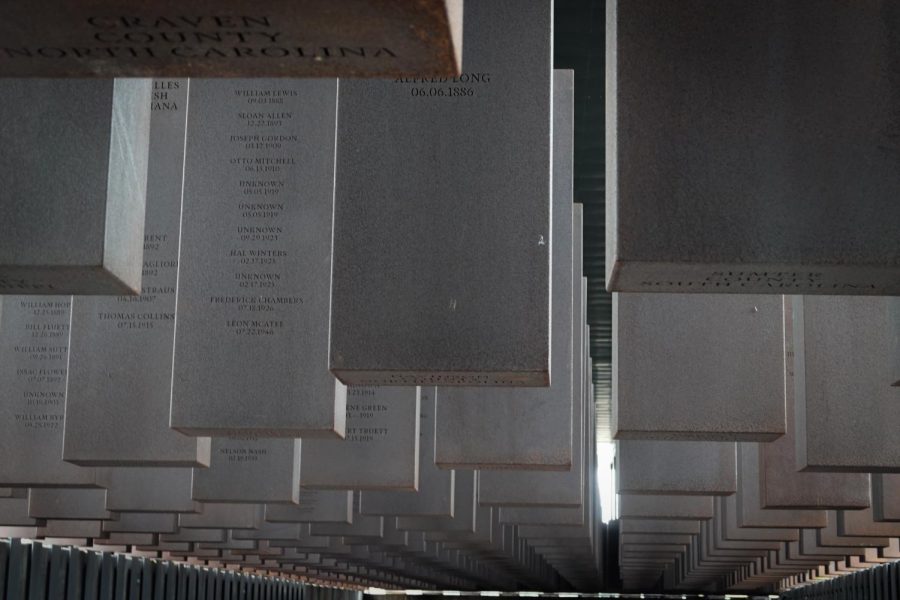

Our next stop was the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, an outdoor memorial commemorating the Black victims of lynchings in the United States. Suspended corten steel columns in the memorial square represented the different counties where at least one lynching had occurred since 1877. Some columns had only one victim named (if their name was even documented), while others had more than 30. The total column count was well over 800.

We then visited the Dexter Parsonage Museum. This restored parsonage, which served as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s residence in the late 1950s, was bombed during the fight for civil rights – the scar in the concrete is still visible today. Fortunately, no one was injured. The bombing drew national attention to the movement, and to Dr. King’s firm stance on nonviolence.

That night, we went bowling at Bama Lanes and got a much-needed chance to wind down after a day of being immersed in such tense and traumatic material.

We left Montgomery for Selma the next morning, a nearby city also rich in Black history. We crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on foot. This bridge was the site of the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches and Bloody Sunday. Not too far away was the National Voting Rights Museum, which chronicles the artifacts and testimonies of the activists participating in the events leading up to the marches.

I came away with so much from the trip; calling it a transformative experience is an extreme understatement. Considering my background as a Nigerian-Canadian, I’d never learnt much about Black history in the States. But since coming to Vandy, American history has affected my life as a Black student here in numerous ways.

I wasn’t the only one. No two Black people in America share the exact same experiences, and the students and staff who came on the trip came from a variety of diverse backgrounds. As I heard said by my chaperone group throughout the trip, “Black is not a Monolith.” In my chaperone group alone, we had representation from Haiti, Mississippi, Nigeria, Canada, and Detroit.

Everyone’s different backgrounds and upbringings meant that we could all bring our own unique perspectives to the conversation. Everyone had different reasons for going on the trip, varying knowledge of the different aspects of Black history and, of course, individual ideas about what it means to be Black at Vandy. The sharing of ideas was beautiful and enlightening and allowed me to come away with many new points of view.

Overall, the Immersion Excursion was a resounding success. The students who went not only left more informed and wiser but closer to one other. Black Vandy has always been an incredibly strong community here on campus, and this trip has only strengthened our relationships.