Last semester, I had just finished writing a big essay, and nervously checked Brightspace to see how I was doing in my classes. After looking at every class and running some calculations, I discovered something interesting. In spite of having received similar grades in all my classes, the requirements to receive an A varied drastically.

Across the five classes I took last semester, there were three distinct grading scales used. I either needed a 93%, 94% or 95% to receive an A. While the difference of 1-2% may seem inconsequential, it can make a world of difference. When the minimum for an A is 93%, there’s some wiggle room to get a B+ on an assignment or two, but when it ticks up to 95%, there’s little room for error on anything.

The whole situation seemed amiss. I knew some classes had a reputation for being easier or tougher than others, but it seemed absurd that something as standard and objective as a grading scale would be so uneven.

Over the course of three months, I investigated the grading policies of over a dozen departments, sent out over 30 emails to Vanderbilt faculty and read over 50 syllabi. There was little clarity, accountability or consistency. I found a university filled with departments and professors individually trying to do what was right, with little consensus along the way. I found a series of varied, unclear and ever-changing rules governing the academic foundations of the university.

I found that Vanderbilt students’ GPAs — held in high regard both within and outside of this institution — have been mangled by the university’s own grading system, leaving them robbed of their significance.

Decentralized decisions

Vanderbilt does not have a universal, mandatory grading scale. While this grading policy is similar to many of its peer institutions, Vanderbilt’s discontinuity in grading is detrimental to student success.

The only university-wide guidance in setting grading scales comes from the Center for Teaching, a department that helps faculty with many aspects of teaching, including the development of their grading scales. Many departments and faculty members take advantage of their services. For example, Dr. Julie Johnson, associate chair for the Department of Computer Science, stated that her department uses the Center for Teaching to guide new faculty on how to structure their grading systems.

Over the course of three months, I investigated the grading policies of over a dozen departments, sent out over 30 emails to Vanderbilt faculty and read over 50 syllabi. I found a series of varied, unclear and ever-changing rules governing the academic foundations of the university.

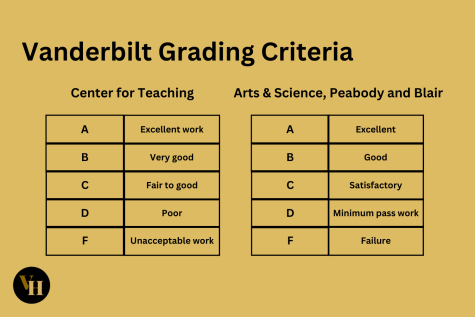

While it can be a great resource for faculty designing or revamping their grading scales, the Center for Teaching provides only guidance — not guidelines — for grading. They also provide very few specific suggestions in their support. Nowhere is this situation more clear than in its extremely vague recommendation for grading criteria, which states that “excellent” work deserves an A whereas “very good” work should only earn students a B. There are no guidelines given for professors to distinguish “excellent” from “very good” work.

The Center for Teaching is not the only party attempting to define the grading scale. The College of Arts and Science, Peabody College, and Blair School of Music provide different guidance in comparison to The Center for Teaching on the meaning of undergraduate letter grades. The School of Engineering’s guidance is less specific, only stating “A, B, C, and D are considered passing grades. The grade F signifies failure.”

This guidance is shallow and empty, yet even here we can see how little consensus and consistency there is. Vanderbilt’s undergraduate colleges and faculty assistance center have not even reached agreement about whether “good” work deserves a B or C — and that is before anyone has even attempted to define what “good” means in a class setting. This lack of guidance leaves departments and faculty to fend for themselves when setting their grading scales.

Some departments, like African American and Diaspora Studies (AADS), have adopted uniform grading policies across their classes, according to an AADS syllabus (AADS 1010) from Fall 2021. Dr. Tiffany Patterson, AADS department chair, confirmed that this policy sets the minimum cutoff for an A at a 96 per the syllabus.

Other departments give professors full autonomy in setting their scales, such as the Department of Economics, per Dr. Joel Rodrigue, vice chair of the department.

Still other departments have found a middle ground, where department leaders provide guidance but leave the final decision up to each professor. For example, Dr. Leigh Scheer, director of undergraduate studies for Peabody’s Department of Psychology and Human Development, stated that this approach is taken by her department.

Every department comes to its own conclusion about how best to handle grading. From what I have seen, it is clear that professors approach these decisions with the best intentions for their students in mind. However, with each professor and department setting grading standards individually, the entire system is left in disarray. As such, the meaning of students’ GPAs are eroded, creating a convoluted system for students, future employers and institutions to navigate.

Scattered scales

Students have to navigate a disjointed labyrinth of grading systems. Vanderbilt encourages its students to take classes in multiple departments, which means learning a new set of grading guidelines and facing different expectations in each course for the same quality of work. At any given time, a student could easily be taking classes across four or five different departments that all have different grading systems.

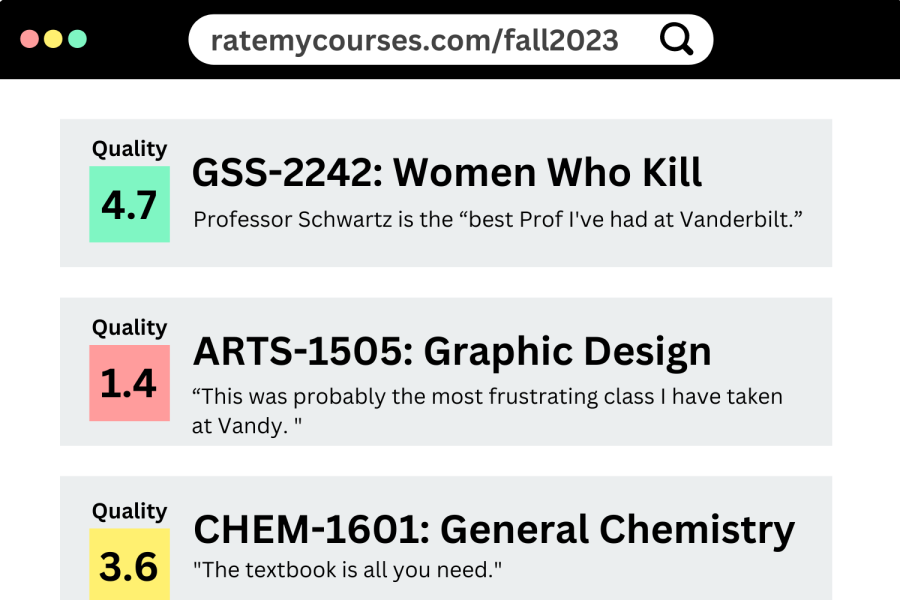

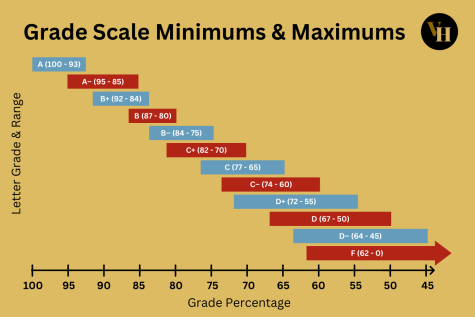

The clearest way to see how much variation persists in these scales is to look at the possible ranges for each letter grade. I analyzed over 50 Vanderbilt course syllabi and found that grade ranges overlap dramatically here, a problem that would not exist under a unified grading system. I found the most variable overlap to be in the range of 60-62%. If a student earns a percentage in this range, there are at least five possible letter grades they could see on their transcript depending on the class: C-, D+, D, D- or F.

Vanderbilt grading scales have become so inconsistent that they may even vary across different sections of the same class. An example of this inconsistency is clear in HOD 2700: Public Policy — a required class for HOD majors and the class that initially sparked my investigation — where the minimum for an A can range from 93% to a 95% depending on the section and instructor. It is clear that the ease with which an A can be achieved may come down to the professor who’s writing the rules.

A difference in scales is not the only problem students face when seeking consistency and transparency about their grades; many classes don’t even provide students with full grading information. The most common version of an incomplete scale is when only letter ranges are stated and plus/minus ranges are determined later. Another far too common and far worse occurrence is that no grading scale is given. In these courses, students may not find out how any of their work has translated into a letter grade until it shows up on their transcript.

GPA cannot provide any useful window into a student’s academic achievements since it doesn’t factor in the systems used to determine those grades. Yet, we still use it as the main metric to represent academic achievement.

These inconsistencies only scrape the surface of the chaos governing Vanderbilt’s grading policies. Rules regarding curving, extra credit and rounding grades are also varied. Some classes use unique and complicated systems to determine students’ final grades, involving multiple configurations of assignment weightings, conditional formulas or rubric-style systems. There are even classes that have completely alternative grading systems like collaborative grading where students argue for the grade they feel they deserve.

While I do not doubt each department and professor has their own reasons for setting their policies as they do, the hundreds of individual inputs mold into a convoluted conglomerate that leaves students disoriented.

When students aren’t given the grading scale for a course, they don’t know what they’re working toward. This lack of transparency also decreases professors’ accountability. How can students under these systems understand how to succeed?

In the end, students are left in a difficult and unfair position.

The great unequalizer

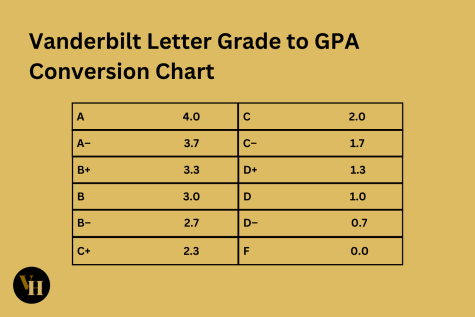

Ironically though, the most atrocious part of this system comes when the university takes all of these different models and attempts to standardize them into one measure. At the end of every semester, final letter grades are converted into GPAs. Unlike the rest of the system, this step is completely standardized and applied uniformly across the university.

As a result, the integrity of Vanderbilt’s grading system buckles under the weight of its many disjointed policies. If grades simply served as a way for professors to provide feedback to students about their progress, individual policies would be annoying and confusing, but they wouldn’t have any major bearing outside of the classroom. But, because the letter grades students receive do affect something larger, the story changes.

Unequal grading scales being given equal weight results in students being either advantaged or disadvantaged based on the classes they took. This means that two students with the same GPA could have performed completely differently in their respective courses. Even worse, it creates the potential for a higher achieving student to have a lower GPA based on nothing more than the rules of the major department or the whims of their instructors.

This removes the value in using GPA to judge students as there is a strong possibility that it does not accurately represent them. If every letter grade means something different, then culminating them into a single metric is useless.

GPA cannot provide any useful window into a student’s academic achievements since it doesn’t factor in the systems used to determine those grades. Yet, we still use it as the main metric to represent academic achievement.

The fallout

GPA may just be a number (and a fairly empty one at that), but it still matters. We’ve been told time and time again not to freak out about our GPAs. Vanderbilt has been communicating this message so loudly and for so long — the first time this school told me about how employers won’t care about my GPA was during my sophomore year of high school at an information session.

Because of this predominant attitude that a grade is just a number, students can feel guilty when we care about our grades. Many of us feel tremendous pressure to refrain from discussing grades with professors for fears of seeming grade-obsessed.

However, just because a mantra is prominent does not make it true. When companies prescreen applicants based on GPA, being only 0.01 below a 3.5 will have an application thrown out before a human ever gets to read it.

There can be serious consequences for a poor GPA. If it falls too low, Vanderbilt can remove students from positions in their organizations, revoke financial aid and merit scholarships and even expel students from the university altogether. A low GPA can cost students and families benefits such as discounts for everything from auto insurance and student loans.

Many students also have other reasons to strive for good grades. For those looking to obtain graduate-level education, GPA will matter. Many also want to make the Dean’s List, earn Latin Honors or just achieve a personal GPA goal before graduation. Even the Center for Teaching agrees that grades can serve “as a source of motivation to students for continued learning and improvement.”

With students’ finances, education and futures at stake, the norm of inconsistency and confusion in grading policies becomes particularly concerning. Just because GPA has lost its meaning at Vanderbilt does not mean it has stopped mattering, and students are the ones who bear that burden.

GPA and educational achievement — two goals that are supposed to support and enhance each other — fall into conflict at Vanderbilt. Instead of GPA serving as an accurate evaluation of academic performance, it becomes a game that many of us don’t want to play but feel we must.

This game is why it has become common to hear things like: “I’m taking a weed-out class this semester so I also want to take something to boost my GPA” or “That class seemed interesting, but it requires a 96 to get an A so I dropped it.”

With students’ finances, education and futures at stake, the norm of inconsistency and confusion in grading policies becomes particularly concerning. Just because GPA has lost its meaning at Vanderbilt does not mean it has stopped mattering, and students are the ones who bear that burden.

While achieving perfect grades is not what education should be about, this behavior is completely understandable — bordering on necessary — given the circumstances. Students aren’t infantile or entitled when they take steps to protect their grades; they are reacting strategically to the predicament the university has put them in. Our goals, finances and futures — all of it may be on the line. If taking a class for “the easy A” every once in a while helps support their objectives, students may need to — and should — do it.

Cutting through the chaos

There are a lot of factors at play here, and I would be overly idealistic and naive to say there is a quick fix to this issue. However, the current system needs fixing, and there is plenty that can be done to improve it.

University administrators need to take incremental steps to increase consistency and clarity in grading scales. Maybe it’s too difficult right now to determine if the minimum for an A should be a 93, 94, 95 or 96, but there are smaller, less complex places to start changing policies. Creating consistent rules on rounding or requiring all professors to announce grading standards at the beginning of the semester — and holding them accountable for doing so — may be good places to start improving the situation.

In my opinion, this latter suggestion is crucial. Communicating grading policies to students means posting a comprehensive guide of their grading scale on the syllabus at the beginning of the semester and being transparent when scales shift or change due to class performance. While some professors already do this, far too many still do not. This standard is a simple yet massive step forward in making students aware of what is expected of them and what they are working toward in each class.

Students can take steps to hold their professors accountable by asking for clarification on the grading scale — especially if it is absent from the syllabus. This proactiveness is particularly important for students’ ability to assure they’re being graded fairly. In extreme cases, a clearly stated grading scale may support a student (or protect a professor) during a grade appeal. Students should have a right to clarity and transparency in their education. When that transparency isn’t provided, we need to ask for it.

The grading system at Vanderbilt is in disarray. It leaves students and faculty without guidance and it has robbed students’ GPAs of their meaning. Students will continue to suffer the consequences of these policies until they are changed.

For that, I give Vanderbilt’s grading system an F — whatever that means.