Three days before school closed for good, I cried over a history paper.

I was struggling to evaluate the impact of Cuba’s economic policy on the emergence of Castro’s authoritarian rule. I had piles of notes beside me and a page littered with sentence fragments staring up at me from my desk. I had written college supplemental essays all night and started on the paper just after 1 a.m. As morning approached, I kept writing, promising myself that I could probably squeeze in a nap during a free period. I watched the sun rise, shut my eyes and wished for time to stop. I wanted everything in the world to stop moving so I could finish my paper.

I would do anything to take that wish back.

The morning that school closed for good, I sat with my friends on the back lawn behind our math classroom. It was unseasonably warm for early March, and we had just finished a test. We lay in the grass talking about college, the future, prom dates and walking across the graduation stage in a few short months. For three and half years, I had sacrificed weekends and stayed up long nights working toward a bright future. I’d gotten through calculus, learned to speak French, discovered a love for biology and finally finished my paper on Castro’s policy. For the first time in a while, it felt like things were coming together.

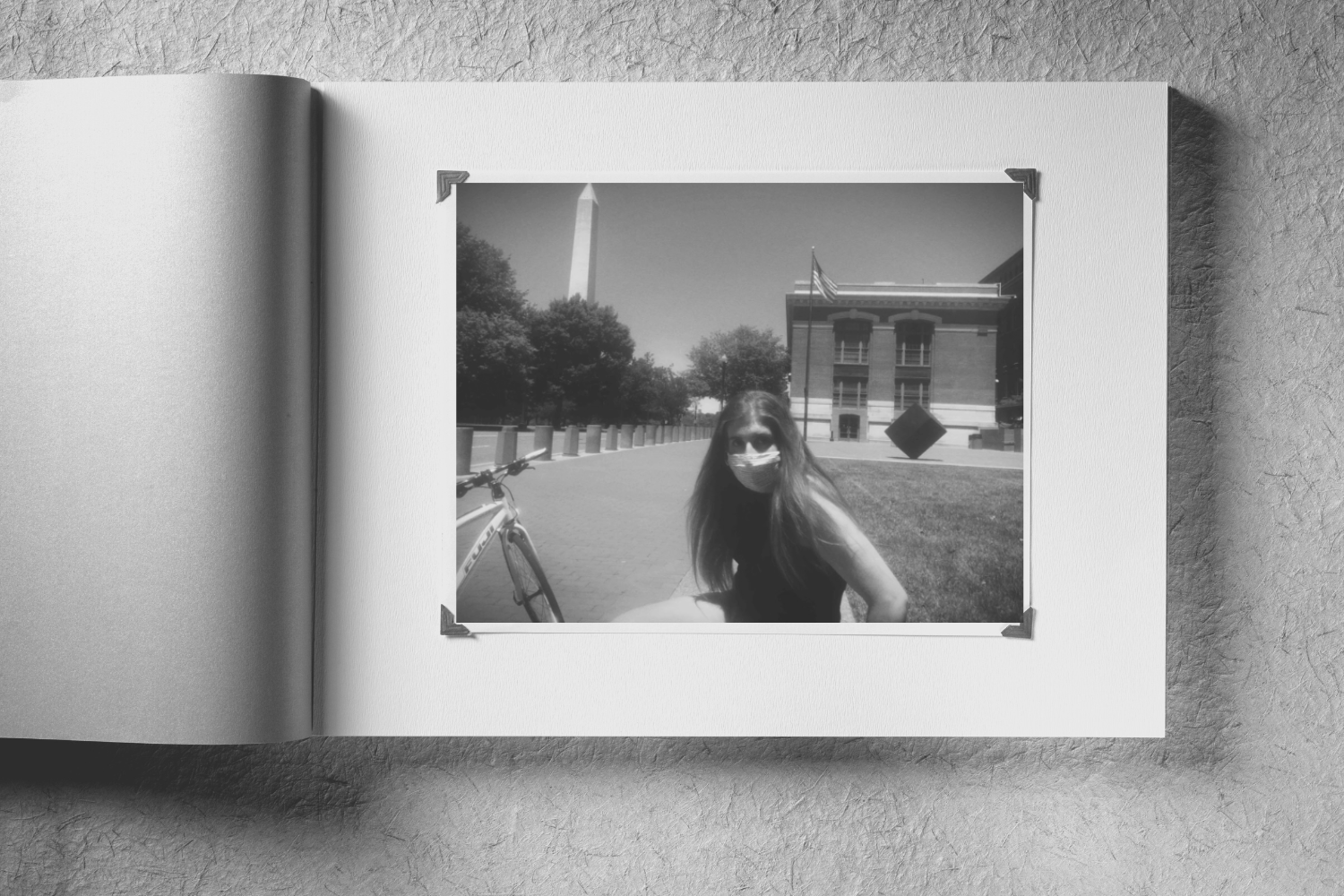

My best friend rolled over in the grass and took a picture of me on her phone. My head is tilted backward and I’m mid-laugh, holding my hand out to block the camera. The photo, overexposed and full of sunlight and warmth, is my memory of the last time things were normal.

Three years later, I am made up of missed memories: birthday candles blown out alone, adventures that could have been, best friendships that faded away and cousins who grew up in pictures. I went from 18 years old to 21 while I watched the world stop moving from my bedroom window.

There is a reason we celebrate firsts and lasts; they provide us closure. The lasts that we normally celebrate–last exam, graduations, last day of school–were absent or abrupt, marked by awkward video congratulations and promises of events to come. The firsts we normally celebrated—birthdays, words, kisses, anniversaries—were put on hold and even skipped over. There were beautiful, defiant attempts to make them special: backyard photoshoots, internet pomp-and-circumstance and elaborate cakes. But then we forgot and moved on.

There are high school friends I saw in math class on the unofficial last day of school–people I haven’t been able to speak to since then. Our separation from the normal into the unknown was blunt, brutal and painful. It felt like putting your head underwater for the first time as a child learning to swim, unsure and terrified of the new world you’ve found. There were many hard days after March 13, 2020, when I would have given anything to be a little late on a history paper without the looming threat of a global pandemic.

At times, it feels like my pre-pandemic life is still frozen in time. There are still some moments when I forget everything that has happened and imagine that I am waking up on a Friday in March 2020 for school. If I walked down the hallway at high school to my locker today, I’m convinced I’d still find an iced coffee, a biology textbook and my P.E. clothes. Sometimes it feels like I fell asleep in my childhood bedroom as a senior in high school and woke up two years into college. I am more than halfway done with my time here, yet somehow just now experiencing my first normal year at Vanderbilt.

My first year at Vanderbilt taught me the value of ritual. On days when I could barely understand the sadness in the world around me or the textbook in front of me, ritual kept me going. I learned how to get up in the morning and put one foot in front of the other. Sophomore year taught me that a year only has as many moments as you can remember. Junior year (and Ferris Bueller) is teaching me that life moves fast; if you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it. But I’m afraid I already have.

Seeing a new class on move-in day with nervous smiles, overbearing parents and way too many plastic bins is a sobering feeling. It is exciting and optimistic and full of promise; yet, at the same time, it is a blunt reminder of the steady march of time. Every new student is a reminder of the beauty of new beginnings and, simultaneously, the ways in which they didn’t happen during the pandemic.

The growing pains of coming of age during a pandemic make it hard to watch new classes have the experiences for which I once longed. It is hard to watch them experience how things were before everything changed. I don’t want to be jealous. Jealousy is a heavy feeling, tinged with guilt and despair. I want to be excited, as hopeful for the future as each of them, bursting with possibility. But faced for the first time this year with the prospect of “life after Vanderbilt,” it is hard to ignore that we missed out on time, memories and closure.

I have my memory to thank for my place at this school. My ability to draw the structure of benzoquinone or recite Lady Macbeth’s “Out, Damned Spot” is a privilege afforded to me by a memory that has always served me well. Yet, somehow, I can hardly remember a day of my first year here. Or the spring that followed. It feels like a dream just after you’ve woken up and you can’t quite recall what happened or who the characters were– but you know it happened. I’m sure I too experienced good times during my first year here but the masks and secret hangouts and late-night study sessions have blurred together.

I’m jealous of the normality of everything. I’m jealous of the memories first-years will make without the presence of a pandemic. I’m jealous of their ability to have friends in their rooms without the threat of disciplinary action. I’m jealous that they never knew about giant arrows plastered on the floor or pre-boxed to-go meals or walking a mile twice a week to stick a plastic swab in your nose. I’m jealous (although relieved) that they won’t have to experience 10 days alone in a quarantine dorm that feels more like a psychological experiment than a public safety measure. Jealousy feels guilty, ugly and unbecoming–but it is also a reality for many of us.

One of my mom’s favorite songs is Lee Ann Womack’s “I hope you dance.” We’ve spent many car rides on the winding roads of Northern Virginia, where I grew up, belting this song on the radio. I remember my mom singing with her entire heart (albeit a little off-key) and telling me about how this song reminded her of her sister. The song narrates a mother’s wish that her children embrace life to its fullest, take a chance on love, loss, wonder and faith and dance every moment they can. As my own sister prepares to graduate high school this year and the Class of 2026 enjoys so many moments I missed out on, this song’s tagline echoes in my mind. Their entries into adult life will not be as heavy as mine. They will have every chance this year to make memories, experience the world and dance, and for that, I’m grateful.

To the first-years who moved into Vanderbilt this year, my hope is that every second of the next four years will be all that you imagined and more. I hope you never have to hear the sentence, “This was better before COVID.” I hope you fall asleep watching movies with your friends way past your high school curfew without worrying about getting them sick. I hope you lose your breath from laughing too hard without worrying about wearing a mask. I hope you stay up late and talk all night and fall in love and smile at strangers—and see them smiling back at you—just because you can. I hope your dorm rooms are plastered with pictures of memories of your senior proms and your best friends from high school. I hope you have a completely “normal” yet extraordinary four years full of light and love and maybe just a reasonable amount of stress. I hope you look back on your first year here and know you lived every moment of it as fully as possible.

Most of all, when you get the choice to sit it out or dance, I hope you dance.

2024 student • Oct 30, 2022 at 10:10 pm CDT

i had to stop reading this the first time i tried because i realized that i was going to cry in the class i was sitting in. this touches the exact spot in my heart that holds the pain of the past few years, and it lays it all on the table so accurately. thank you for taking your gift of writing and helping to share the feelings so many people can empathize with.

anonymous • Oct 16, 2022 at 8:27 pm CDT

So beautifully written Zoe. I’ve felt so guilty for being jealous of the incoming grades, and never felt as seen as I did in this. You are amazing

Abigail Kwon • Oct 3, 2022 at 1:05 pm CDT

so so beautifully written zoe. completely changed my perspective on my first year at vandy—thank you for your vulnerability and authenticity <3

Bonnie • Oct 3, 2022 at 10:32 am CDT

Beautiful and touching. I’m so sorry that everyone your age had to go through all of that. You explained the pain of it so well. Much love and wishes for a bright and happy future ahead for you.