“We could not find a record with the information you provided.”

I sighed in frustration. It was the summer of 2021, and I finally decided to tackle the long-overdue task of renewing my driver’s license. For what seemed like the hundredth time, I pounded my name and ID number into the online form. And once again, the red pop-up window glared back at me.

Why do I not exist?

Annoyed, I examined my driver’s license yet again—and that’s when I discovered a typo in my name.

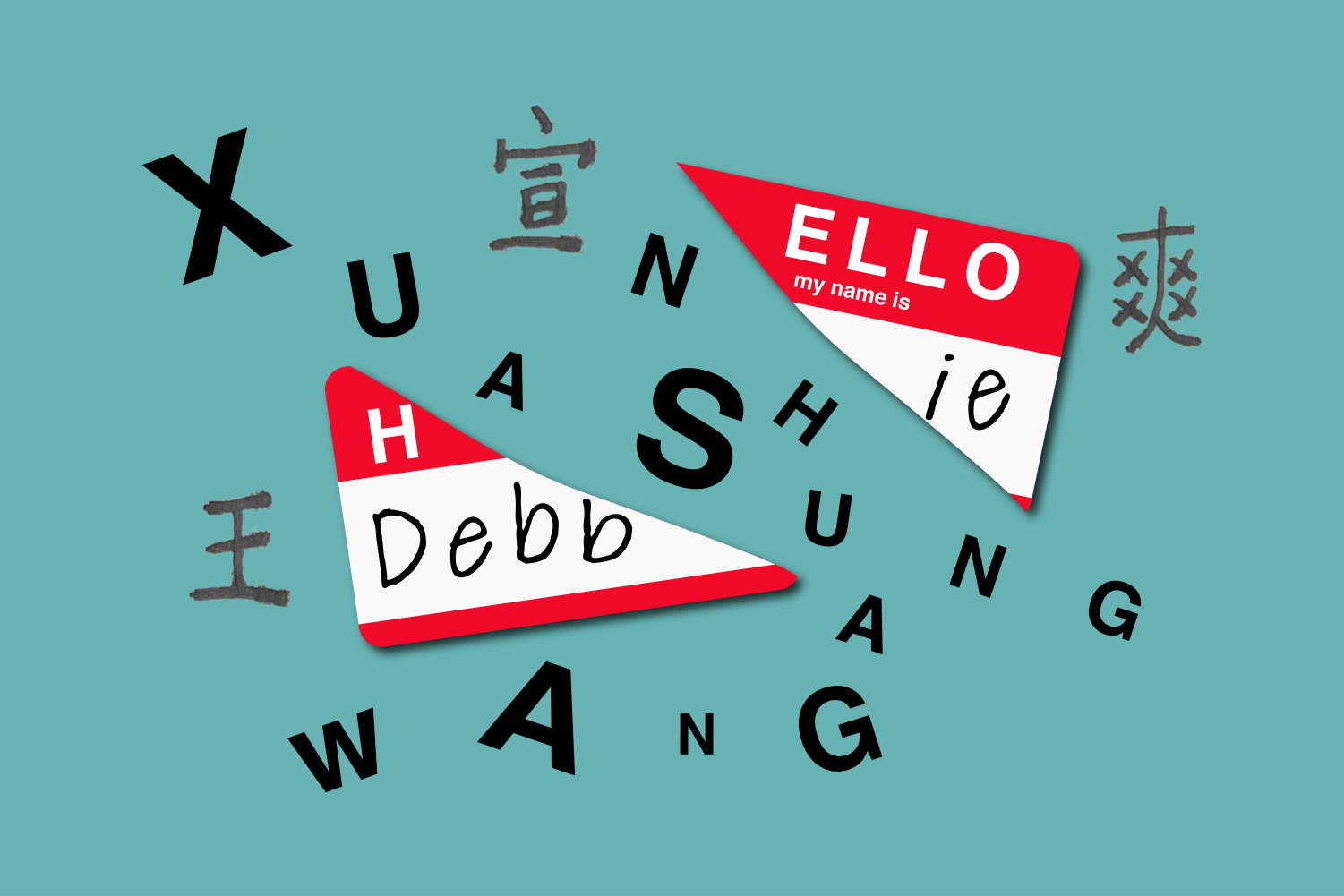

“Debbie” is not my legal name. Under the impression that my Chinese name Xuanshuang would be too difficult to pronounce, I adopted the name “Debbie” before entering the sixth grade in America.

Fuming about the State Department of Licensing’s incompetencies, I typed in the misspelled name—and sure enough, my license was renewed. However, the shock that I had carried an ID with a misspelled name for the past four years felt truly disorienting.

“Learning to pronounce a colleague’s name correctly is not just a common courtesy but [also] an important effort in creating an inclusive workplace, one that emphasizes psychological safety and belonging,” wrote Forbes reporter Ruchika Tulshyan in an article titled “If You Don’t Know How to Say Someone’s Name, Just Ask”. The argument goes that if one can learn to say Hermione or Eisenhower, they are also capable of pronouncing Liu or Yichen.

Truth be told, questions like “how do you pronounce your real name” have always made me wince. As others awkwardly tried—and failed—to say my name, the burden fell on me to correct them. The effort exhausted me. After a while, I simply tolerated the mispronunciation.

Sometimes, people I meet will say things like, “I’d love to have a unique name like yours.” Contrary to their belief, having a one-of-a-kind Chinese name does not give one leverage in this country. Nine times out of ten, others forget my name almost immediately. In their minds, I’ve vanished into “the girl with the weird-sounding name.” Growing up, I loved being the second or third “Debbie” in a classroom—at least this way, others would acknowledge me by my name.

“Mutilating someone’s name is a tiny act of bigotry,” educator Jennifer Gonzalez wrote in a 2014 blog post. Pronunciation matters. A 2012 study published in the Harvard Business Review found that the microaggressions associated with the mispronunciation of names often cause Students of Color to internalize the message that they don’t belong. Over time, the derived shame and dissociation hamper students’ emotional well-being and academic success.

The driver’s license debacle was not an isolated incident. Whenever I apply for a new credit card at the same time as my sister, the bank always rejects our requests on the basis of “duplicate application.” You tell me, do our Chinese names – “Xuanqing” and “Xuanshuang” – sound alike ?

Then there are the daily inconveniences: being popcorned last on a Zoom call, running out of space while bubbling in my name on a standardized test, having to spell out my name two or three times for the receptionist and the list goes on. As others butcher my name, I’m drowned by the feeling of otherness.

In The Namesake, author Jhumpa Lahiri describes a Bengali-American protagonist tormented by his name: “At times his name, an entity shapeless and weightless, manages nevertheless to distress him physically, like the scratchy tag of a shirt he has been forced permanently to wear. At times he wishes he could disguise it, shorten it somehow.”

I, too, have struggled with such waves of uneasiness. Growing up, I developed the habit of preemptively raising my hand before a substitute teacher read my name off for attendance. To this day, attending events on campus still triggers a wave of anxiety, even though I know that Vanderbilt uses “Debbie” on all its rosters. In high school, a friend asked me whether my parents had given me my “English name.” I told her yes. In reality, I had picked the name “Debbie” myself, vaguely thinking that it sounded sweet and short. For the longest time, I was embarrassed by my two names—the English one for being too simple and the Chinese one for being too complex.

Of course, I don’t expect anyone to say my Chinese name perfectly on their first try. Yet, it’s one thing to mispronounce, another to flippantly disregard one’s blunder. Bit by bit, offhanded mistakes such as the misspelled name on my driver’s ID chip away at my identity. On the other hand, I am equally irritated by people who dive into an hour-long grandiose conversation about “the beauty of your culture” after learning about my Chinese name. I’m simply craving for allies— individuals who listen first and truly practice the pronunciations later.

Perhaps due to the recent rise in public awareness of anti-Asian racism, many Asian-Americans have opened up about their own struggles with an unconventional name. In a recent interview with USA Today, Asian-American actor Simu Liu, who plays Marvel’s newest superhero Shang-Chi, acknowledged that he had wanted a more Anglicized name as a child. “I gave my parents a lot of crap and asked, ‘Why didn’t you just name me ‘Steve’ or ‘Tommy?’” Liu explained.

Conversations generated by such candid revelations give me hope that one day, America will learn and remember our names.