When I first became an earth and environmental science major, I failed to make the connection between race and climate change. I, like many, mistakenly believed that climate change only impacted wildlife. I did not yet fully understand the deeply rooted issues of climate change that have burdened marginalized communities for centuries.

I also have come to realize that the climate change movement has been whitewashed. When talking about conservation and preservation, very few people outside of the impacted groups (from teachers to activists) actually talked about the importance of protecting Black and brown communities and their connection to the environment. This is because many of the institutions that push for climate activism have historically been majority white and thus more likely to exclude people of color. One study showed that on average 95.4 percent of the board members were white across 191 conservation and preservation organizations. Minorities only consisted of 12.1 percent of new hires in these organizations. By comparison, in the year the study was published, ethnic and racial minorities made up 38 percent of the United States population. This means that Black and brown perspectives are largely underrepresented in environmental organizations.

Race is not a separate issue from climate change. Black and brown communities have faced past and present injustices that have made them more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. For example, New Orleans’s predominantly Black Lower Ninth Ward experienced some of the worst flooding from Hurricane Katrina, and recovery has been much slower than in white neighborhoods. Because climate change is the direct result of colonialism, imperialism and slavery, communities that are most affected by climate change are also most affected by police brutality and inherited racial trauma.

Most significantly, the age of Jim Crow resulted in housing and infrastructure policy favoring white, wealthy homeowners, enforcing segregation by class (and therefore, race, because white supremacy has forced BIPOC communities into a self-perpetuating cycle of poverty) and trapping Black and brown homeowners in poorly maintained neighborhoods for decades. Neighborhoods that were predominantly Black and brown were situated mainly in sites that white people deemed uninhabitable or useless. The goal of many of the housing policies that came out of the 20th century was to keep people of color out of white neighborhoods in order to preserve property value.

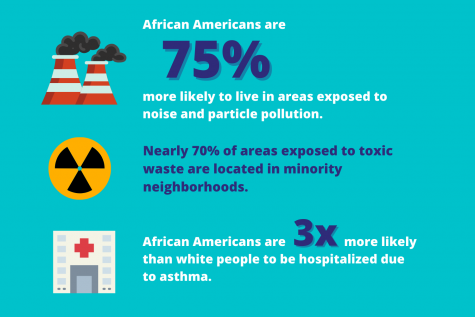

The legacy of these racist housing policies still exists today because of the self-perpetuating wealth gap between predominantly white neighborhoods and neighborhoods consisting mainly of people of color. Approximately 57 percent of Black and brown people live in counties with higher levels of ozone and particle pollution. They are also more likely to die from conditions caused by pollution and toxic substances. As a result, marginalized communities disproportionately suffer from upper respiratory issues and other health problems, as well as flooding and other climate hazards, because they have been forced into developments in are as exposed to highly polluted water and air.

African Americans are 75 percent more likely to live in areas exposed to pollution, and nearly 70 percent of areas exposed to toxic waste are located in minority neighborhoods. Because of this, African Americans are three times more likely than white people to be hospitalized due to asthma. Some corporations still seek these neighborhoods to dump waste or pollute the air because it is cheaper to do so.

In Nashville, majority BIPOC neighborhoods east, southeast and north of downtown Nashville labeled as “hazardous” by the Home Owners Loan Corporation in the 1930s were less likely to be allowed to get a mortgage, preventing residents from being able to accrue wealth. Many environmental hazards exist in these areas because the lower property values attract polluting corporations and highways. Residents of the James A. Cayce Homes, public housing in East Nashville that is 90 percent Black, suffer from the highest rate of asthma in Nashville due to air pollution, pollution from Interstate 24 and Toxic Release Inventory facilities in the area. The James A. Cayce Homes demonstrate that BIPOC communities disproportionately suffer from pollution because of racist housing policies originating from the 20th century.

Beyond just living in toxic environments far from basic necessities, many Black people in America have been systematically killed due to physical oppression and police brutality. This loss of life means that less people are able to advocate for Black needs in climate change policy.

As environmental justice activist Elizabeth Yeampierre put it, “If we couldn’t breathe, we couldn’t fight for justice.”

Police brutality leads to an increased fear of retribution in minority communities. This fear of police can prevent people of color from advocating for their needs or going to climate protests, meaning white voices are more likely to be heard in climate justice movements. Furthermore, felony disenfranchisement of Black and brown bodies can result in an inability to vote for government officials who have their needs at heart. Without a true advocate in government or in activist groups, the climate issues that arise for Black and brown communities are not accounted for enough in climate change policy.

The climate movement and future climate change policy will not be effective without Black and brown voices.

That means that colonialism, slavery, police brutality and racism need to be addressed and accounted for in order for the climate movement to be effective. Centuries of systemic racism need to be undone. Climate advocacy and policy needs to be more inclusive and accessible for minority communities. Organizational standards and requirements need to be equitable, not equal. Cultural norms need to be inclusive and supportive.

We cannot uphold conservation of the environment without incorporating marginalized voices because they have always been an essential part of nature. Their perspective is invaluable to the climate policy of current and future generations. It is imperative that Vanderbilt earth and environmental science and environmental sociology majors and sustainability minors take classes that focus on the intersection of climate justice and racial justice. You cannot have an understanding of environmental science without understanding racial issues facing marginalized communities. The next generation of environmental science graduates need to be well-versed in racial justice issues in order to properly begin solving climate issues.