Rev. Teresa Smallwood, J.D., PhD currently serves as a postdoctoral fellow and associate director of the Public Theology and Racial Justice Collaborative at the Vanderbilt Divinity School. From public ministry to legal services, Dr. Smallwood has employed an intersectional approach towards addressing systemic racism, using law and theology to aid in her quest for social justice. Dr. Smallwood is a recipient of the Henry W. Edgerton Civil Rights Award and has served several educational roles, investigating criminal justice, religion in North America and other academic disciplines. Here’s what Dr. Smallwood had to say about her work and her goals for the Vanderbilt community and the United States at large:

Vanderbilt Hustler: What kind of activist work are you involved in and what roles do you have in the organizations you are engaged with?

Teresa Smallwood: I came to Vanderbilt’s Divinity School as a postdoctoral fellow and an associate director of the Public Theology and Racial Justice Collaborative. Within that group was a charge to develop collaborative partnerships, to be a part of the work going on in the community and to build partnerships among that group of people.

So immediately upon hitting the ground, I began building a relationship with the Interdenominational Ministerial Fellowship joined up with my church. I am a member of New Covenant Christian Church and was most recently named social justice minister there. And so through those connections with my work and with our Social Justice Ministry, I’ve been involved in lots of what I call activism.

How do you see public theology?

I see public theology as living your faith out and racial justice as dealing specifically with the kinds of things that people who are racial minorities bump up against in their capacity to live a public life in America. In Nashville, for example, I have experienced people who have been displaced because of gentrification or natural or financial hardships. So my work has centered around how to help people manage and overcome some of those kinds of hardships.

How have the tragedies in Nashville over the past couple of years impacted your work?

My work is funded by the Henry Luce Foundation, and they gave a million dollar grant to the Divinity School to create my program. As a result of the economical challenges due to COVID, the foundation also gave us $150K to distribute to organizations we have partnerships with to mitigate the calamities different folks were facing. We work with about 15 groups, and they are not just confined to Nashville, though a number of them are located here. I’ve worked with partners all over the nation, but specifically in Nashville, we’ve assisted two church entities that were devastated from the tornado last year by developing a relief center where we created a tent and fed people through the coordination of local restaurants and addressed any other acute needs. In short, my activism is about trying to spread the love I feel in a very popular city where people are really struggling.

Was there a defining moment in your life that motivated you to become involved in activism?

I’ve been engaged in activism since I was a young kid. I grew up in Windsor, North Carolina, and saw evidence of how education could get me out of that rural setting. I knew from living there what it meant to be an impoverished, marginalized person, but what I didn’t understand was how that fit into the world view of racial politics. When I went to UNC Chapel Hill as an undergrad, I began standing with anti-apartheid actions and taking position against injustices that I saw. I went on to Law School for the purpose of being able to advocate and articulate for those who had been cast aside and whose voices were silenced. In my professional work, I started out as a public interests lawyer, trying to protect people from being manipulated by big corporations. Then I went on to the District Attorney’s office to work as an assistant, understanding that prosecution does not mean persecution.

It was only when I went to get my Master’s degree from the Divinity School at Howard University that I became engrossed in the notion of disparities. I became really involved in the District of Colombia once I saw how law enforcement in regards to marijuana and drug use was coming out of two specific areas with high minority populations. It wasn’t a popular field to venture into as a person of faith, but it was the right position to take to stop the disparities and bleeding.

Do you think your desire to join the Vanderbilt community stemmed from your passion to address the health disparities that exist within Nashville, or was there another motivating factor?

One of the reasons I decided to come to Vanderbilt was Reverend Emily M. Townes. She stands tall when it comes to the academic fervor of knowledge production. She has dealt with some of the most important issues when it comes to how we see the cultural production of evil and has written extensively on health disparities. The Henry Luce foundation came to her because of her work with the idea of the Public Theology and Racial Justice Collaborative and she took the offer and created for me what was the perfect job.

The second reason I’ve come to Vanderbilt is because of Nashville itself. I have been in awe of the fight for freedom and survival that takes place here. What drew me here was recognizing Vanderbilt as a southern institution where good work is taking place and where there is a committed effort for good towards equity and diversity and inclusion. I felt that my efforts would be welcomed and that I would find a place of belonging.

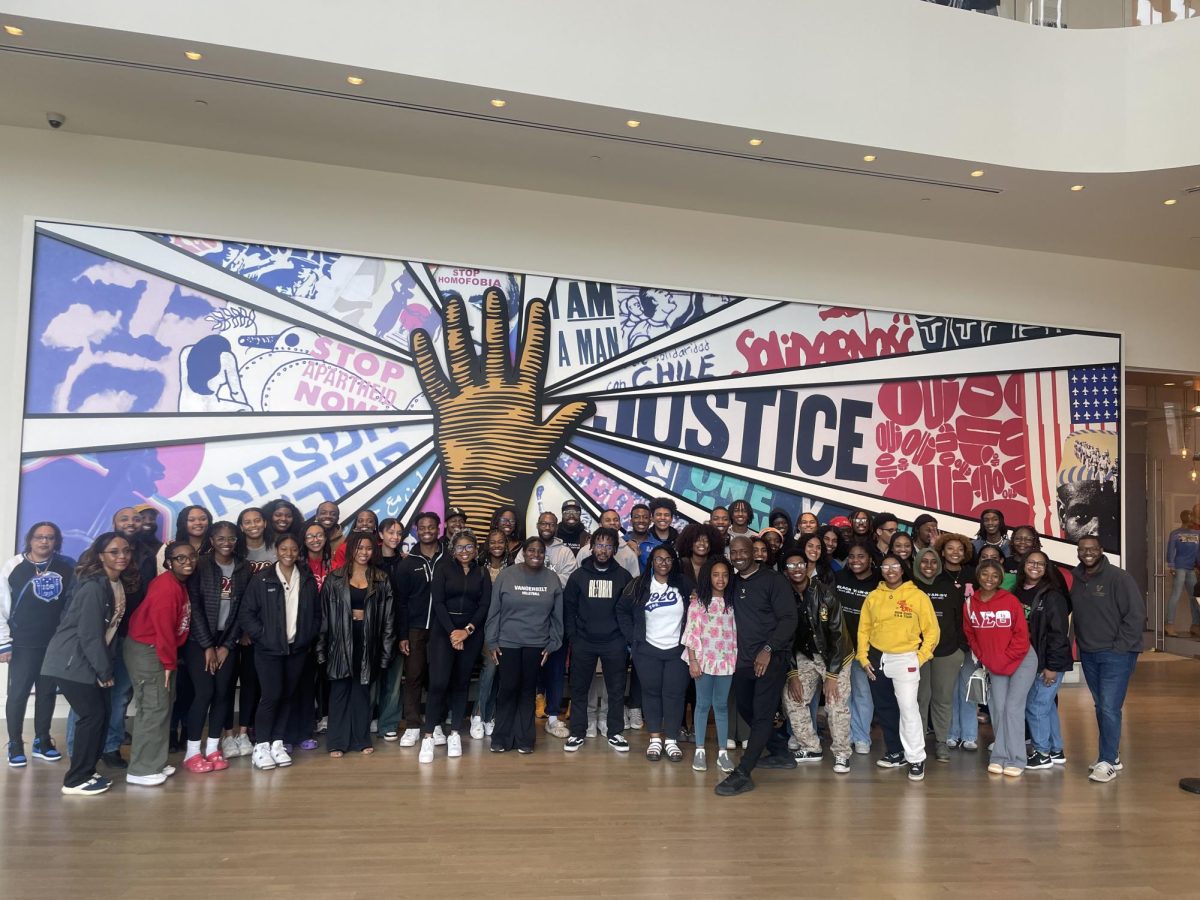

What are your reflections on Black History Month and the current activities at Vanderbilt?

I understand the importance of Black History Month as a celebratory moment and what was won, but for me, every month is Black History Month. I have been thoroughly impressed by the work done by the Black Cultural Center. What is clear is that Vanderbilt has learned from its historical records. For instance, we are all waiting to get vaccines, and there are underlying disparities in the accessibility of them alone, but the Vanderbilt Medical Center is displaying a concerted effort to try and get things right. We have a long way to go, and I know we can do better in our statewide leadership as it relates to how we deal with the needs of people. People are trying their best to spread love, and although the government sometimes fails us, when we organize and activate ourselves through our faith, we find the light.

Is there anything you would like to say to Vanderbilt students to motivate them to be more engaged in activism?

A lot of us have taken note of the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and countless other people, and we tend to look at them as isolated incidences of situations in which people have come up against a bad experience. But even in Nashville, we have our own stories, and so it is important to underscore the systemic nature of racism. Baked into the United States’ institutions are ideas of how criminality is overlaid for some people, and it shows up in our healthcare system. To combat that, we need a strong common will, and if young people take action, they can move the political will to do what’s necessary in efforts to change the trajectory of racist ideologies.

When you think of someone who says “I can’t breathe,” that is a public health declaration. If the reason they can’t breathe is because a racist ideology is keeping them from doing so, then there you have it. That’s evidence of how we must work to bring health disparities out of the mainstream and into a place where they can be harnessed and dealt with. Our efforts need to cut across socioeconomic lines in all communities of those who face the worst of outcomes, because people should be valued over the interest of capitalism.

Responses have been edited for clarity and brevity.