Fitzgerald. Austen. Vonnegut. Hemingway. Shakespeare. Orwell. Salinger. Bradbury.

These are the authors whose works I was required to read in high school. The voices who comprise the Western literary canon as most students are taught it. The representatives of classic literature. The messengers of the wisdom we are supposed to gain from books. Not a single one is Black.

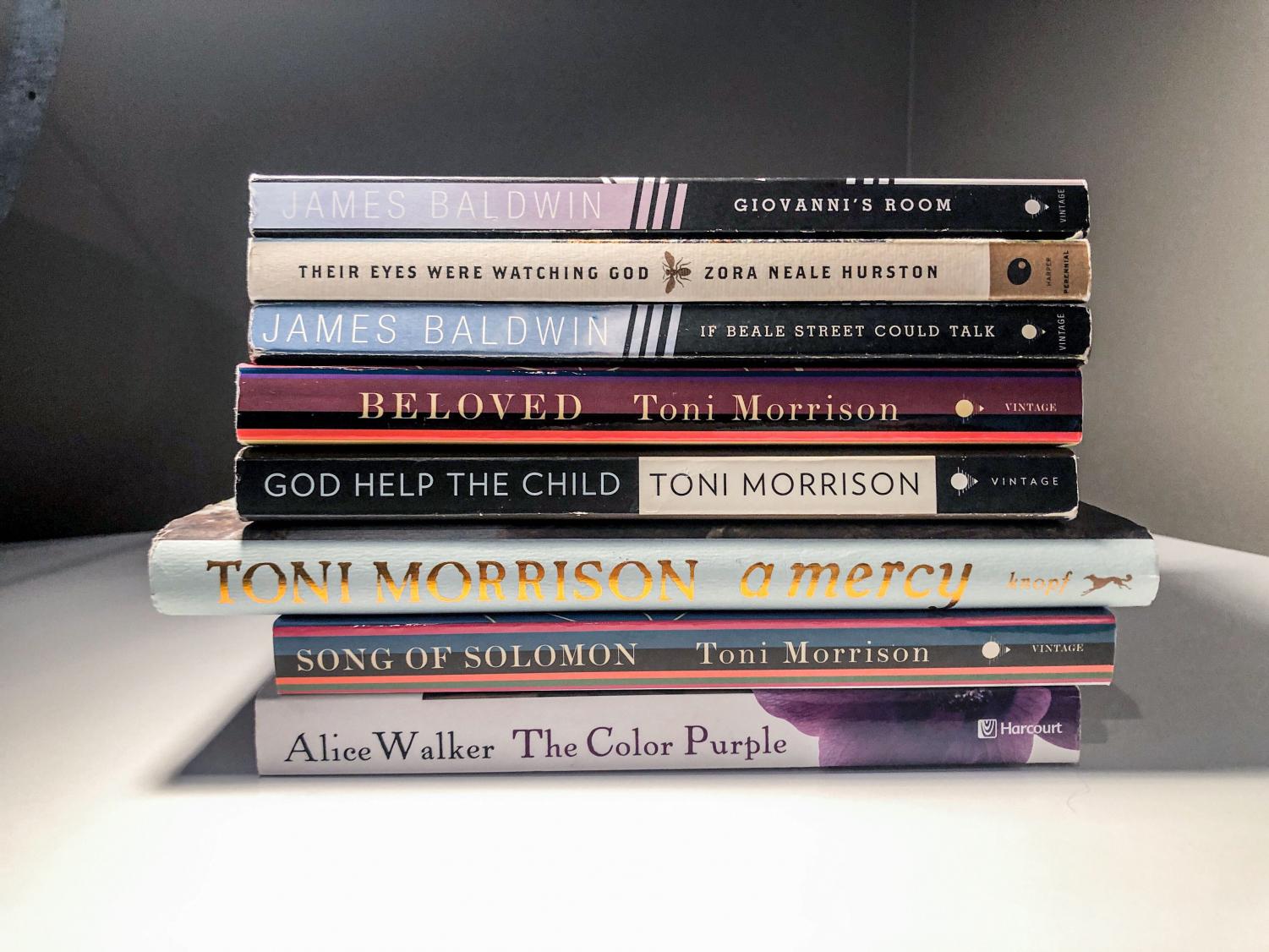

At one of the most competitive high schools in New Jersey, no one told me to read Black authors. No one quizzed me on them, assigned papers on them or facilitated class discussions on them. Our curriculum turned its back on the literary prowess of authors like Toni Morrison in favor of the few white voices from whom we hear so often, granting exclusively one demographic the responsibility of speaking to the human experience in America and beyond.

And so we wrote our papers on “Hamlet,” heard way too much from Holden Caulfield and took Fitzgerald’s America as our own. We read about white people, talked about white people and wrote about white people, and no one told us we should do anything more. Many of my peers in high school went off to some of the best colleges in this country without having once been required to engage with Black literature.

I will always be grateful to Zora Neale Hurston for opening the door for me into the side of American literature that my high school curricula, which had been rich in other ways, hadn’t incorporated. As a white woman in an overwhelmingly white suburb, my blind spots were immense, but I slowly but surely began to see that they were there. Reading “Their Eyes Were Watching God” for the first time, and bearing witness to protagonist Janie Crawford’s life as she navigated questions of race, class, identity and power, led me to appreciate the distinct role of literature, particularly fiction, as an educational tool. Hurston’s novel situated Black female identity in a framework that felt tangible—Janie wasn’t a footnote in a history textbook, or a point in a debate, but rather a person I was getting to know, and growing to love. Perhaps it’s a function of my learning style, but something about sitting alone with the voice of another—whether a writer or the characters they have crafted—reifies the theoretical into the personal, material convictions that drive empathy and solidarity.

So with every intentional effort to diversify what I consumed, I stepped farther and farther away from the whitewashed version of the Western canon that fails to celebrate the diversity of writers and experiences this country has always possessed. Identifying my own knowledge gaps by reading Black authors—and recognizing that there is a sea of literature out there to confirm even more—has helped me realize that the most important part of allyship is being able to learn with the awareness that you will never know. As readers, this means learning from, loving and honoring Black characters and stories with the understanding that there are millions of iterations of them we can never begin to imagine.

I’m writing this to demonstrate that ignorance of Black experiences is often the default, that if you don’t seek out the voices and novels and words of Black writers, chances are, no one will expose you to them. You can ace high school English classes and sound “well-read” and think you know the first thing about American literature when you have actually been ignoring so much of it. I’m writing this to tell white Vandy students that we are so privileged to learn about racism not from experience, but from novels and poems, short stories and memoirs. So we must read them. We must hold novels like “Sula” with the same regard that we do novels like “Little Women,” not only because they deserve it, but also because if we don’t, we fail entirely to complete one of literature’s most fundamental goals: to understand lives that are different from our own.

Over the past week, I’ve been thinking a lot about a quote by James Baldwin: “The paradox of education is precisely this—that as one begins to become conscious, one begins to examine the society in which one is being educated.” As I educate myself on issues of systemic racism in America, I grow more and more resentful of a society in which this failure to confer such essential histories, experiences and voices to young people is possible. But we need to do more than bemoan lost time, time in which Black Americans were, and still are, facing racial realities while we were shielded from them. We need to close the gap.

So to all of us whose upbringings didn’t challenge us to seek out some of the most beautiful, essential pieces of American literature: we can’t recover the time we spent ignorant of racial issues in America, but we can put our time in now. We are in quarantine, likely with hours upon hours to invest in becoming better allies to the Black community at this moment and always.

White Vandy students: I implore you to spend this crucial time, and the rest of your lives, reworking your definition of “classic American literature” so that it goes beyond Thoreau and Hawthorne and people who look like them. I encourage you to grant a fraction of the effort you have spent studying white writers to honoring the works of Black writers. Learn from Pecola in “The Bluest Eye” about the oppressive beauty standards whiteness can bear or from Rufus in “Another Country” about Black masculinity. Read the works of Kimberle Crenshaw, who gifted us the lens of intersectionality, and those of other Black feminists, like Audre Lorde and Angela Davis, from whom we should draw inspiration in all of our feminist efforts. Use this political and cultural moment we’re in right now to educate yourself, celebrate Black writers and honor the literature we too often fail to.