According to “Affirmative Action for the Rich: Legacy Preferences in College Admissions,” a 2010 book containing chapters by various attorneys, reporters and students, and the Common Data Set, Vanderbilt originally took legacy status into consideration for admissions then reported dropping this practice. Vanderbilt did not consider legacy status during the academic years spanning 2005 to 2007 and began considering legacy status in admissions once again during the 2007-2008 academic year. This places Vanderbilt with the 42 percent of private institutions that consider legacy status in admissions decisions.

As admission to top universities becomes more competitive each year, the smallest differences between applicants can mean the difference between acceptance and rejection. By placing importance on factors such as legacy status, qualities of an applicant’s profile that are outside of their control can make or break their application.

Vanderbilt considers legacy status but does not explicitly state the required level of alumni relation in order to be considered a legacy in admissions. Students must self report their relation in their application.

At Vanderbilt, legacy status is considered at the same level as other non-academic factors, such as geographical residence, volunteer experience, work experience, first generation status and racial/ethnic status, according to the website for Vanderbilt’s Office for Planning and Institutional Effectiveness. This makes it more important than demonstrated interest and religious affiliation, factors which are not considered, according to the Office for Planning and Institutional Effectiveness website, but less important than extracurricular activities, personal qualities and talent/ability.

While legacy status is considered in admission, there is limited public information on the extent that legacy status helps an applicant, and statistics on the demographics of each year’s legacy class aren’t made publicly available.

According to Dean of Admissions Douglas Christiansen, Vanderbilt strives to find the best students to make up each incoming class, regardless of legacy status.

“As we review applications, an alumni affiliation is just one data point among many, and it is not a dominant factor by any stretch of the imagination,” Christiansen said. “Students must be academically ready to be here and have the experience and background to add to our community.”

Legacy-preference policies have received criticism for benefiting groups historically advantaged in the college admission process. Christiansen declined to disclose demographic statistics on the incoming legacy class.

In addition, Christiansen declined to comment on the benefits or drawbacks of including legacy preferences in the application process.

“We love taking alumni legacies. They accept our offers at a higher rate than others, and the whole family usually has an affinity for the school,” Christiansen said in a 2015 article published by the university called “The Big Search.”

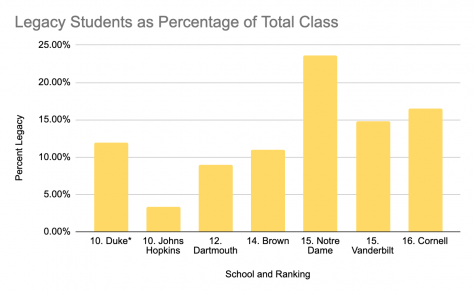

According to Christiansen, 14.8 percent of Vanderbilt’s class of 2023 are legacy students.

“[This] puts Vanderbilt on the low end of that percentage among our peers,” he said.

However, out of the seven schools ranked between ten and 20 on the U.S. News and World Report that have legacy preference and publish statistics on percent of legacy students in each class, Vanderbilt has the third highest percentage of legacy students. Vanderbilt follows Notre Dame at 23.6 percent for the class of 2022, and Cornell at 16.7 percent for the class of 2023.

Out of Vanderbilt’s peer institutions, Johns Hopkins has the lowest legacy population, with legacy students making up just 3.3 percent of the class of 2022. Brown and Dartmouth also have lower rates of legacy students, at generally 10-12 percent for Brown and nine percent for Dartmouth’s class of 2023.

In Feb. 2018, Vanderbilt alum Ravi Guru Singh published an article in Inside Higher Ed, calling on Vanderbilt to end legacy preferences. He made this call in light of Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard, a lawsuit claiming that Harvard “unconstitutionally engages in racial balancing by keeping the number of Asian students artificially low in order to admit more Black and Hispanic applicants.”

As part of the lawsuit, Harvard was required to disclose demographic data on legacy applicants, where it was revealed that the acceptance rate of legacy students was five times that of non-legacy students, and that legacy preferences strongly benefitted affluent, white applicants.

Singh asked Vanderbilt’s admissions office to release race and gender statistics of the legacy class but was unable to obtain the information. He told The Hustler in an email that legacy preferences stand in the way of a meritocratic admissions system, and that questioning the institutions is the first step to reversing this policy.

“What happens with legacy preferences, is leading up to a student’s admission to the school, the [alumni] family will donate more money to the school in the hopes that it would help them get extra consideration,” Singh said. “If the kid doesn’t end up getting in, the alumni donation rate from that family drops off. So what ends up happening is de facto bribery, where families are trying to get as much of a leg up as they can using money instead of merit to get their kid into the school. That’s anti-meritocratic and it’s anti-democratic to me, and not what I believe in for America.”

Singh graduated from Vanderbilt in 2011, and he began studying the impacts of legacy preference policies as an attempt to embrace equality of opportunity and make institutions of higher education accessible my merit, not hereditary factors.

Singh currently works as an associate at the law firm Paul Hastings. He graduated from Northwestern School of Law in 2015.

“If the goal of a university education in this country is the further understanding of truth, of knowledge, of community, then legacy preferences needs to go because it doesn’t build those things,” he said.

Legacy preference hasn’t always been a factor in university admissions. Legacy preference policies started in the 1920’s as a way to protect elite universities like Harvard, Yale and Princeton from the influx of Jewish and Catholic applicants. And although these policies have evolved since their inception, they will always be connected to these exclusionary roots.

According to Singh, legacy preferences are hereditary privileges for primarily affluent, white students, whereas affirmative action serves to address historical inequalities and discrimination.

“Unlike affirmative action, which is a race-conscious and gender conscious preference (one of the biggest benefactors of affirmative action is white women), legacy preferences are facially race-neutral, Singh said. “So there isn’t an explicit preference for wealthy white students, it just so happens that they end up benefiting disproportionately. From a legal perspective, it’s a little more difficult to bring a case against legacy admissions. It’s easier to bring a claim of racial discrimination than it is for something that’s more focused on familial ties.”

Despite the lack of transparency from Vanderbilt about the demographics of the legacy class, Singh continues to fight to start conversations about the structural inequality that legacy preferences bring to college admissions. Singh has pledged to donate $5,000 to Vanderbilt if it agrees to end legacy admission preference. His pledge remains symbolic of his commitment to make college admissions as meritocratic as possible.

With his donation, Singh said that he isn’t hoping to counteract donors supporting legacy preference policies on his own. Instead, he is calling on alumni to join him and make their own contributions, using their donations to signify their commitment to ending the policy of legacy preference.

“Can we step up and promise to make up the shortfall?” he asked.

Correction: This article has been changed to represent more precisely the date that Vanderbilt reported changing its policy on considering legacy status according to the Common Data Set. This article’s headline has also been changed to reflect the fact that legacy status is one factor considered in admissions.