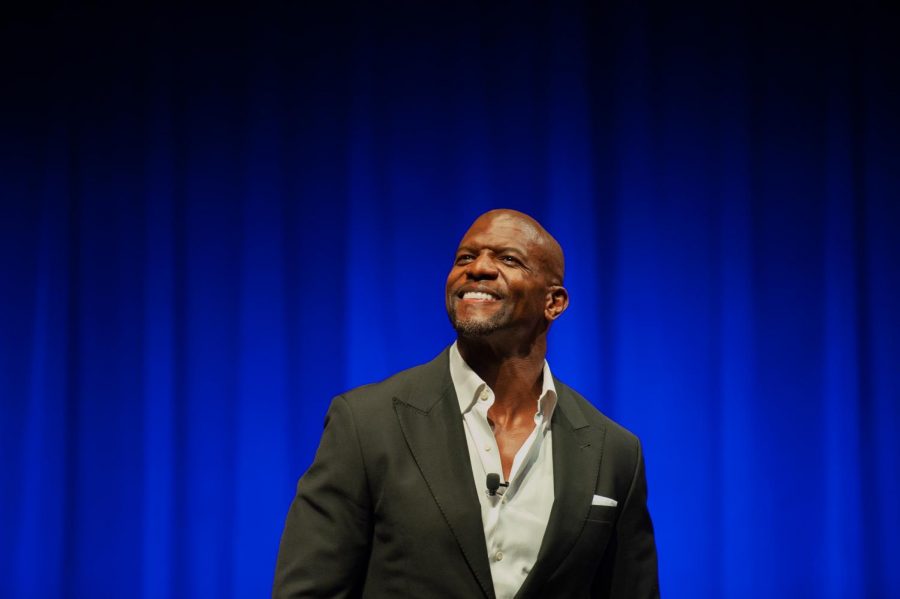

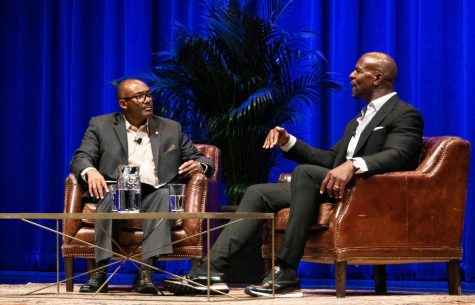

Terry Crews came to Vanderbilt Sept. 9 to discuss his personal journey to becoming a champion for women and healthy masculinity in a Chancellor’s Lecture Series event titled “Reframing Masculinity and Gender Equality.” Following Crews’ talk was a Q&A moderated by Interim Vice Provost for Strategic Initiatives William H. Robinson. Crews credits his wife, Rebecca King-Crews for playing a huge role in his personal growth.

His visit to Nashville was in partnership with the SHIFT conference, the first-ever national event focused on bringing about cultural change in the areas of healthy masculinity and violence against women. The conference, which took place Sept. 9 and 10, is put on by the YWCA of Nashville and Middle Tennessee and was organized by Vanderbilt Alumnus Shan Foster.

In 2017, Crews was named one of TIME magazine’s “Silence Breakers” for his openness about his own experience of sexual assault while supporting women speaking up and encouraging others to believe women engaged in the #MeToo movement.

Vanderbilt Hustler: So, you are a man of many talents. From skilled artist to professional athlete, award-winning floral arranger to flautist, interior designer to famous actor, pitch man and also an outspoken advocate for a healthier culture in regards to toxic masculinity and sexual assault. Which role has been your favorite? Is there anything you miss?

Terry Crews: All those things you mentioned are like my children. It’s like, do you have a favorite kid? I literally love everything I’m doing right now because I kind of created a rule where I only do what I love. And it’s funny – just the other day I completed a TIE Fighter from Star Wars in Legos. And I loved it! Everyone was like wait – first of all, you don’t get any money for this? Everybody thought it was an ad. I’m like no, this is all me – my wife will tell you I was obsessed with it.

There’s something beautiful, to me, about creating. And about bringing something into the world that did not exist before. And that’s why I think I’m totally built for Hollywood. Because it takes time and energy, but when the finished piece is done, you can really enjoy it. So, I won’t say anything [I’ve done] is my favorite.

VH: I understand that you’re in Nashville for the YWCA SHIFT conference. Can you talk a little bit about the SHIFT conference and why it matters to you?

TC: We need to change the picture of what masculinity is, and we also have to take responsibility as men for our role in the mistakes. I spoke this morning [at the conference] about the issues that I had being at toxic male myself, being caught in a web of not knowing what true manhood was. Because that is the question most men are just trying to figure out: What is a man? A lot of people will tell you, “Be a man,” but most have no idea what that means. And that definition just falls all over the place.

When they say “Be a man” it means: be what I want you to be. What’s really wild is that I was guilty. I had truly believed that because I was a man I was more valuable than my wife, simply because those are the rules of the world. And it was my way or the highway, and I really didn’t have a lot of other options. There was nothing else to look at when I grew up in Flint, Michigan.

Every man I knew had this kind of attitude of “Man, look, you better run your house and you better run your wife.” It was almost a view of ownership, men that owned their families. You didn’t share, you weren’t a team. You were a CEO. You were an owner. Anything less than that, they would call you whipped. Say, “Oh man, you’re a punk.” Say, “Oh you actually let your wife talk to you as if you’re equal?” And I fell for it. My wife would call me on so many things. She would say, you’re not gonna call me that, you’re not gonna treat me like that.

And I have to say, this is what’s so wonderful about what helped me to move along and to grow is that my wife never, ever put up with any of my B.S. She never did. She was always calling me on who I was, asking: What kind of man are you? Who do you want to be? This is not right, you have to treat me this way. And I remember thinking, ”Why don’t you just get with the program?” And she never did. To be honest, her courage is what saved our whole family. Her strength is just one of those things that saved me.

It’s kind of like a cult, and I like to call it the ‘cult of masculinity’ because you’re in it, hook, line and sinker. And the cult members support each other. You know, when I first came out about my addiction to pornography, I had really prominent men come up to me and say “Hey man, what are you doing? This is man talk, you’re telling all our business!” That is something you would say to a cult member.

There were so many things that I had to question. I got turned around and said, this is not the way that it is supposed to be. It’s like cracking an egg. And once an egg is cracked, you try to seal it back, but you really can’t. It just keeps cracking. And it all culminated with the sexual assault that I endured by the head of the motion picture department at my own agency. And my wife was right there. This was after years of growing and learning. My wife had left and we had rebuilt our marriage; I went to rehab and totally regrouped. We spent 10 years reassembling our lives, and then this happens. The toxic thing kept rising to the surface and it was like a culmination. And that was it. With that, we said “This is the hill that we’re going to die on.”

VH: I was impressed by your restraint in that situation – How did you have such self-control?

TC: My wife had made a deal with me because I’m not known for self control. She’s been with me for thirty years. The first twenty years of my marriage she’s seen me throw people over her head, she’s seen me get in fights. She’s seen me knock people out. She pulled me aside and said “Terry, you are a black man in America. If you react this way, you’re either going to jail, or going to get shot or you’re gonna get killed.”

She said, you have to promise me that you’re not going to deal with anything like this in a violent way. I said okay, and it was the best promise. That promise saved my life, because imagine I had hit this guy. Who would have believed me? Who would have believed that this guy touched me first? No one would have believed that. No one. I remember asking [the head of the production company] William Morris if they would’ve had mercy on me if I had hurt him. And the head of William Morris looked at me and said, “No we wouldn’t have had mercy on you Terry, not at all.” I have to say my wife has taught me how to think my way out of situations, as opposed to fighting my way out.

VH: Rebecca, this next question is actually for you. Can you talk a little bit about where your strength comes from— your dedication to doing the right thing and guiding your husband to a better path? How did you remain so committed?

RC: Well, there are several things. We got married young and when I met my husband, I had one of those serendipitous epiphanies about him. I dated in high school, I dated in college and by this point I knew what I wanted and didn’t want in a person. And I made a list and sent that list out to God and said I want this kind of person. And so when I met Terry it was like, “aaaaa” [singing].

I was very committed to him because I felt like I had been given what I had requested. Terry and I were students when we met, so when we got together we were broke. So if football didn’t work out, I was still committed to Terry, the guy from Flint who charmed his way into my life and became my best friend.

As a young adult I found my own way back to a form of faith in Christ, which then took me on my own journey of personal growth, development and self-discovery. And one of those tenants is commitment to your marriage vow, the concept of unconditional love. So whether you’re being the best husband or not, I chose to treat you with the love that the scriptures say that God has for us.

He did the really hard work, the really humiliating and humbling work of going to rehab, of going to therapy, of reading the books, challenging his beliefs and listening to other people that had the same problems. Then finally, opening his heart to things that I had tried to say over the years. I will tell you I was shocked. At that point I was doubtful, we were 22 years married and he had been an angry, restless man most of his life.

People say that people don’t really change, but I changed. I went on my path, and after 22 years at 40-something years old, he made a change for the better and not only dealt with his own addictions and issues, but pulled hard to keep the family together. And then he became a voice against the things that turned him into someone he didn’t like and that his family didn’t like. And that’s the greater miracle, that you take the chain that used to bind you, and you use it as a weapon to set other people free.

Responses have been edited for clarity and length.