There’s an oft-told, apocryphal story about President John F. Kennedy when he visited NASA in 1961. The President took a wrong turn and happened to run into a janitor carrying a broom. Curious, President Kennedy asked what the janitor was doing. As the legend goes, the janitor responded with these words: “Mr. President, I’m helping put a man on the moon.”

That janitor, if he ever existed, understood the importance of small things and knew where he could make a difference. He recognized that if he could reduce the clutter, make sure there was enough chalk available for the chalkboards and enough pencils and paper for the rocket scientists, he would have done his part in helping this country win the space race.

Admittedly, in classes here at Vanderbilt, most of us aren’t involved in putting a man or woman on the moon. However, there is no question that what we are doing is important. According to our Academic Strategic Plan, the very document which called for new residential colleges and academic buildings, Vanderbilt is “positioned to educate the next generation of leaders and pursue path-breaking discoveries that address the most pressing problems and questions confronting society.” The plan proceeded to argue that achieving this mission required investments in new building facilities. It outlined the blueprint for all the campus changes we see today, either in progress or completed, from E. Bronson Ingram to the $600 million West End Neighborhood project.

Now, it’s great that our university can, and will, make such vast commitments to our campus’s future. But when we spend hundreds of millions on big, fancy new things, we sometimes forget what the NASA janitor knew: that the small things matter, too.

This principle can be illustrated by something as simple as a whiteboard marker.

Have you ever had a time when a whole class was disrupted by the lack of a working marker? I have. It’s surprisingly distracting.

Last semester, I took a class with Professor Helmut Smith, an eminent scholar of German History. Professor Smith knew his material, and he would frequently create moments during his lecture when he had the undivided attention of every single student as everyone hung onto his every word.

But those moments were often spoiled by the lack of working whiteboard marker. Professor Smith would attempt to put something on the board – and the marker he tried would be dried out. He would try the other markers lying around, which would also fail to work, and eventually, he’d go back to using the first marker, because at least it produced a faint line. And that was better than nothing.

It was frustrating. One could feel all that energy suddenly just sucked out of the room.

There is an unignorable cost associated with this. What’s the point of building million-dollar, state-of-the-art buildings and hiring well-paid scholars if we end up with classrooms with whiteboards but no reliable, working markers?

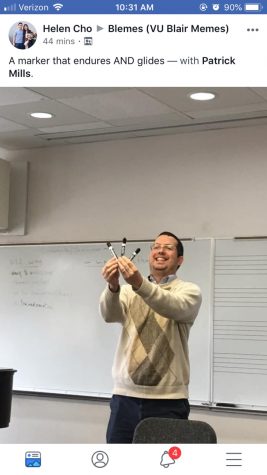

These situations have happened too often, and not just in classes I’ve been in. At one of my friend’s music history classes at Blair, for instance, musicology professor Douglas Shadle’s delightful reaction to finally having working markers became a literal meme.

The marker brand in use at Blair is called “EnduraGlide” by Quartet. According to Shadle, they can dry out in a single class session if not treated with care.

“I use dry erase markers in every class,” he said, “and if they dry out, students get distracted while I scramble to find another. One day, Expo markers appeared in our office supply drawer, and they were far better. It isn’t just my preference for one brand over another – good markers foster greater accessibility and inclusivity for my students.”

As Shadle’s comments illustrate, this isn’t just about markers. It’s about the problems caused when we don’t have reliable classroom supplies, and the benefits we have when we do.

It’s about not having HDMI cable or appropriate adapter available in every room, delaying or preventing an important presentation.

It’s about not having enough chairs in the seminar rooms, so one has to go chair-hunting. (This happened in the aforementioned German History class, due to the scheduling system not foreseeing the possibility that a class might have a few students more than the specified limit).

This is about ensuring that students have the tools to learn and professors have the tools to teach.

It’s about Blair practice rooms without any music stands – stands, not $10,000 pianos or cellos, but $30-$50 music stands.

This is about us, as a university, finding a better system to promote effective work and study spaces. This is about ensuring that students have the tools to learn and professors have the tools to teach.

Of course, with four undergraduate schools, sixty-eight major programs, and almost 7000 undergraduate students, it’s hard to find a one-size-fits-all solution. But nonetheless, these are often simple, solvable problems. There are actions that our school administration can take: it can provide for well-located supply shelves and an accessible budget reserve for students and professors, as well as hire additional maintenance and support staff.

We can look at how respected companies go about reducing some of their daily disruptions. At Google, “grab n’ go” stops (shelves consisting of small tech items like HDMI cables, screen filters and phone chargers), as well as open office-supply cabinets (consisting of items such as whiteboard markers and notebooks), are never more than a stone’s throw away from any employee. Similarly, Facebook offices have vending machines in easily accessible areas, allowing employees who need earbuds or cables to get them for free.

There is no reason why a similar vending supply system, whether it vends for free or for a nominal fee, can’t be implemented on our campus.

Additionally, every undergraduate school can set up a small, openly transparent budget of a few thousand dollars that professors and departments can draw from to better serve students. This budget can be drawn upon for convenience, while also being transparent with respect to who uses it and how much. This would deter bloat and encourage frugal, but effective, usage.

Finally, we must address the possibility that we need a bit more manpower in some places: from janitors to maintenance staff to technicians. The university administration should investigate if this is the case. If it is, it should determine how best to allocate additional funding for ensuring that classrooms have intact chairs and working screen projectors.

Would implementing these steps be too much work to spare professors the occasional small inconvenience? Not at all. It’s clear how quickly these small, daily nuisances could actually add up.

If the university administration can put some spare change to use in order to eliminate these nuisances, this would be a true bargain: such an action would go a long way to improving the quality of learning and scholarship on our campus. Fundamentally, I believe that’s exactly what our university should strive to do.

Winston Du is a senior in the College of Arts and Science. He can be reached at winston.du@vanderbilt.edu.