In the late 1960s, during a time of rising racial tensions and growing dissent regarding the Vietnam war, Vanderbilt found itself at a turning point in its history. Under the leadership of the newly designated Chancellor Alexander Heard, the university opened itself up to diverse and often controversial speakers who reflected the changing campus and American community. Perhaps most notably, Vanderbilt’s 1967 IMPACT Symposium, a student organized event, brought the biggest names in the country to Memorial Gymnasium, giving a platform to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, Strom Thurmond, Allen Ginsberg and many others.

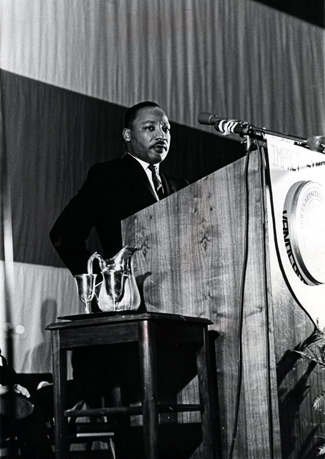

The event came one year before Dr. King was assassinated and occurred just days after King’s Beyond Vietnam speech, for which he was harshly lambasted. At Vanderbilt, he spoke of the status of the Civil Rights Movement, and the long history of oppression that was only slowly being chipped away. Thousands attended the Symposium, and for members of the Vanderbilt student body, the event marked a symbolic change in the university, indicating a move to a more progressive institution with an emphasis on academic freedom.

The Hustler spoke with two alumni from the class of 1969, both of whom were present on campus during what was likely one of the most tumultuous times in the university’s history.

Culture shock

In 1964, eleven years after Vanderbilt admitted its first Black student, Joseph Johnson, to the Divinity School, the first group of Black undergraduates matriculated to the university. Eileen Carpenter arrived at Vanderbilt a year later, in 1965. Excited by the university’s recent decision to integrate, Carpenter was prepared for the typical college experience of socializing, parties with friends and a generally fun environment. While she would find those experiences later on, her freshman year was something of a culture shock, having grown up in a segregated Nashville and having never meaningfully interacted with white people.

The other students, Carpenter found, were largely polite, though seemed mostly to ignore Black students, beyond the occasional small smile in passing. Conversations around diversity and inclusion, an omnipresent topic at Vanderbilt today, were far from the imagination at the time.

“That was a very painful experience for me, when I realized that I don’t really exist here. I don’t matter. People were nice if they if they caught your eye, they might smile or whatever, but you had the sense of I’m not really here, I’m not really a part of this, I don’t really impact anything. So that was certainly my feeling and because I lived at home my first semester, I think my feeling of isolation was felt more intensely. I did move on campus the second semester of my freshman year and it was a lot better, mainly because then I could interact with the Black students. I was taking math and physics classes, which were mostly white guys, and that interaction was kind of a no-no.”

At the time, Carpenter said she had a distinct anger at not feeling fully included as part of campus, and at college not living up to her expectations. Even though she didn’t face outright verbal and physical acts of discrimination, she still did not feel as though she fit in with much of Vanderbilt’s dominant culture.

Moving onto campus and finding friendship with other Black students began to give Carpenter the experience she was looking for. On the eleventh floor of Carmichael Towers, Vanderbilt’s Black students would gather to talk, party, share their experiences and enjoy themselves. It was on this floor that the students started “Rap: from the eleventh floor,” a magazine dedicated to giving Black students a space to speak about their experiences, share their writing and poetry and make themselves heard.

People were nice if they if they caught your eye, they might smile or whatever, but you had the sense of I’m not really here, I’m not really a part of this, I don’t really impact anything.

Carpenter remarked that years later, the class of 1969 still takes pride in their radical reputation, which, while not representing all of the student body, did make a large impact on the culture of Vanderbilt at the time. Chuck Offenburger, who also came to Vanderbilt in 1965, said that there were regular speeches and demonstrations on Rand terrace, and that The Hustler’s editorial pages were filled with letters from students.

“I remember in my freshman year, the Hustler editor writing editorials about the apathy at Vanderbilt. As I flip through the pages, there was even a section entitled “Vanderbilt is dead.” And the jist of it just was, there was nothing going on here,” Offenburger said. “Everyone was doing their own in thing in the Greek houses, and nobody was paying attention. And then the second year, when this Impact came, that changed everything. I think after that, it seemed like just everybody was holding programs and bringing speakers on campus.”

IMPACT 1967

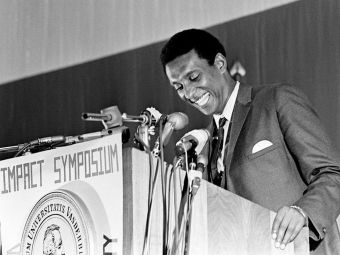

Entitled The Individual in American Society, the IMPACT Symposium of 1967 primarily tackled the racial tensions of the time. In particular, the event brought Dr. King to speak on Friday night, followed by the polarizing Stokely Carmichael on Saturday night.

“We could probably look back and point to that weekend as the moment that Vanderbilt pivoted and really changed,” Offenburger said. “With those two speakers, and with several others who were on that docket for IMPACT that year, it was like the student body’s interest and imagination just mushroomed. From that point on, I think everybody was tuned in and paying attention and very active on big issues. The discussions would start in the classrooms and the frat houses and Rand hall and the classroom and they just never stopped. It was a lively time, and that crossed the campus.”

The two men represented different sentiments in the movement; Dr. King was of a more conservative position and considered more acceptable to white audiences, while Carmichael’s Black power philosophy and more radical stance appealed to younger Black people. Carpenter remembered campus as still very conservative, particularly among the students. She said that faculty appeared to lean more liberal, but she was still surprised by the fact that Vanderbilt had brought someone as radical as Carmichael to campus.

“I remember being really excited and just a bit incredulous that Vanderbilt, as conservative as it was, would put together such a radical group, because there was Stokely Carmichael and Martin Luther King. At that time Martin Luther King went from being considered just totally radical by most whites to being the conservative and preferred one to Stokely Carmichael.”

In the days leading up to the event, the Tennessee State Senate passed a resolution condemning Carmichael’s visit to Vanderbilt, calling him a “dangerously unprincipled demagogue.” Carpenter said they started a petition opposing the state legislature’s stance on Carmichael. Despite the state’s protest, the event continued, which Offenburger said had to do with Chancellor Heard’s dedication to providing an open forum for students to learn.

“[Chancellor] Heard was the most intellectually liberating thing that ever happened at Vanderbilt. He had the classic outlook on education that people who are in the liberal arts treasure, that there should be lively discussion and questioning, and sometimes even controversy but the academic inquiry should be alive and encouraged,” Offenburger said. “Without him, IMPACT would have never happened to what it became, because he gave the okay for that student committee to invite people who were at the highest level of prominence in our society in all kinds of fields. He wasn’t a bit afraid of asking somebody who came in with some controversy to him.”

Following Carmichael’s appearance in Nashville, some fighting broke out along Jefferson Street, which eventually turned into larger rioting. Many in the city, including the now defunct Nashville Banner were quick to blame Carmichael, and by extension Chancellor Heard, for the riots. Carmichael later said in an interview that the riots were instigated by police. The university stood by its decision to bring Carmichael to campus and Heard continued to promote the idea of an open forum for conversation.

“I think that was probably one of the first times in the state of Tennessee where there’d been an issue like that, where the basic premise of the liberal arts was being condemned and questioned,” Offenburger said. “And as soon as the public got aroused, that sort of rallied the students all together to make our stand.”

April 4, 1968

Offenburger was working in the newsroom, then situated inside Alumni Hall, when he got a call from a friend. Dr. King had been shot in Memphis. Offenburger switched on his radio and listened intently as other members of The Hustler came to join him. Frantically, Offenburger tried to call his brother, Tom – King’s press secretary – but was unable to reach him. At that point, The Hustler’s business manager suggested that Offenburger and Mark McCrackin, another writer for The Hustler, go to Memphis to figure out what was going on. Using McCrackin’s mother’s credit card, the two immediately boarded a plane to Memphis to see if they could get to the Lorraine Motel, where King had been shot.

“We could see as we were flying into Memphis that there were already smoke clouds. We didn’t know what was going on, but we assumed there were fires. We went to a cab stand and – you know, two white college kids- we asked this cab driver, can you take us to the Lorraine Motel. That’s really about all we knew, that it had happened at the Lorraine Motel. And he said, ‘Boys, I can’t take you there. The neighborhood is just exploding over there, it’s just too dangerous.’ And I said, ‘If we pay you twenty bucks, can you take us as close as you can?’ And he said, ‘Okay, let’s go.’”

Once at the motel, Offenburger was able to locate a colleague of his brother’s, who said his brother had flown back to Atlanta early that morning. Throughout the night, Offenburger and McCrackin did what they could to help Dr. King’s staff and took notes on the unfolding events. The next day, the two flew back to Nashville to put out a special edition of The Hustler, commemorating King. Decades later, McCrackin wrote an essay about the experience, which Offenburger found and published after McCrackin’s death in 2018.

Shortly after King’s death, riots broke out across the country. Offenburger says he remembers Nashville on fire. The city implemented a 10 p.m. curfew, and Mayor Beverly Briley’s request for National Guard assistance resulted in 4,000 troops pouring into the city.

“We could look out on West End Avenue, and the only thing going down the street were military vehicles and cop cars. We just kept doing what we knew how to do, and that was go be reporters,” Offenburger said. “We went around and found our way over. There was a big National Guard encampment by Centennial Park, a point where they would send troops out to wherever there was trouble. And we went over to Tennessee State and saw some friends over there, and we were gathering quotes for stories in the paper. In fact we had Perry Wallace and one of his great friends, Walter Murray – they became Hustler reporters that night because they had access to places we couldn’t go.”

At the time, Offenburger questioned whether the country was going to survive the tragedy and the aftermath. The school did its best to support students, and over time things returned to normal.

“I’m not sure we even had class for a couple days. The curfew got lifted early the next week and then people started to move about more normally,” Offenburger said. “But subsequent to that there were all kinds of services and marches and rallies around the city and on campus too. Reverend Asbury was leading the way on campus as far as making opportunities for students to be involved as they wanted to be.”

Life since Vandy

In the years since their graduation, both Carpenter and Offenburger have remained connected to the university. Both have returned to campus over the years, for reunions and sporting events and homecomings.

“I’m so pleased when I walk around campus now to see how diverse the student body is in every way, it’s just thrilling,” Offenburger said.

Despite not connecting with many white students while she was at Vanderbilt, Carpenter said in the years since she’s grown closer with other members of her reunion class. She later had a niece attend Vanderbilt, and while her niece’s experience was more diverse than her own, Carpenter said that many of the same problems she had dealt with were still present on campus.

“In this country we’ve we’ve never really addressed the issue of race in a meaningful way. We’ve never embraced the oneness of mankind and until we do that, we’ll all be fractured. I do think we’ll get there one day.”

Michael West contributed to this report.