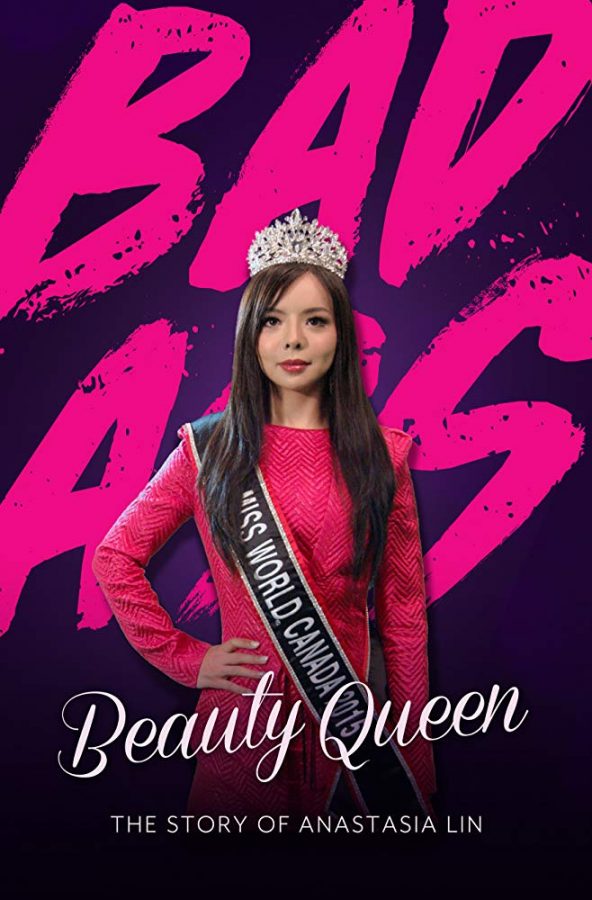

Last Friday, I learned that the film Badass Beauty Queen was scheduled to be screened as one of the events for this year’s International Education Week. The film is based on the story of Anastasia Lin – a Chinese Canadian who is a human rights advocate and practitioner of Falungong, a condemned religion in China. The film has elicited some controversies: a number of Chinese students think the film degrades their national dignity and have been protesting for the screening to be called off.

As a Chinese international student, I do not find these remonstrations unreasonable at first glance, especially given the plethora of the negative portrayals of non-democratic countries that are prevailing on elite US college campuses. The International Education Week is aimed at “preparing Americans for a global environment,” as is shown on its sponsor ISSS’s website, which suggests the main targeted audience of the film are American students on campus, some of whom are white wealthy elites who may have the power to impact Sino-US relations in the future. Considering the political implications of screening a presumably anti-China film in an American-dominated college it may help to create an image that Chinese people are in need of a Western savior. And this will doubtlessly further foster America’s Manifest Destiny. Insofar as I am empathetic with these post-colonial narratives, the remonstrations of my fellow Chinese students resonate with me. But they don’t convince me entirely.

Last summer, I met a Falungong practitioner in person for the first time in my life. It was when I was doing an internship at a law firm that I got to know about Gu. Driven by a sense of curiosity, I engaged in a conversation with her. At the age of over 60, Gu was arrested by the local police for storing certain Falungong publications in her house. In conversing with Gu, I surprisedly retrieved the same feeling I would have if I were talking to a grey-haired granny who was a Christian: she looked so benign and amiable. And I could see a great devotion in her eyes when she was talking about her sacred beliefs. As an atheist, I personally do not believe in any religions, but it was since that time that I began to believe every citizen is entitled to the right of believing a religion, even if it was condemned.

Looking back at my encounter with Gu, it pained me to see how some of my fellow Chinese students treated the human rights issues advocated by Falungong practitioners as a façade for them to spread their condemned religion. To start, most of them had neither any personal interactions with Falungong practitioners throughout their lives nor any first-hand understanding regarding the Tiananmen Square self-immolation event. This event, assumed to be conducted by seven Falungong practitioners, took place in January 2001, when most Chinese undergrads here, including myself, were just pre-kindergarten kids with no consciousness of what was going on.

Throughout the two decades since the event, the Chinese state-run media’s coverage of the Tiananmen Square self-immolation has successfully convinced most citizens, especially the younger generation, that Falungong is a terrorist organization. In their portrayals, followers of Falungong seek to subvert the Chinese Communist government by enticing its practitioners to suicide (even though this conspicuously violates Falungong’s fundamental doctrine – truthfulness, compassion and forbearance). Through mandatory “politics” class and school textbooks, the religion has successfully been branded as an evil cult to the new generation. As a result, the majority of the young people in China firmly believe Falungong is not only an illegitimate religion, but also an anti-China political force inextricably associated with Sinophobic powers overseas.

Driven by such a strong patriotic sentiment, many of my fellow Chinese students tend to feel spontaneous animosity towards the screening of the film in which a practitioner of a condemned religion publicly defies China’s government. I relate to the feeling of defending China against any stereotypes when I am abroad – after all, the last thing I want to do when I am far from home country is to reinforce stigmas around it. Having been born and spent many years in China, I undoubtedly have deep affection for my country: I love its grand and beautiful land, long and rich history, hard-working and kind-hearted people and the Marxist ideals enshrined as a guiding ideology in the Chinese constitutions.

It is exactly this love, however, that pushes me to rethink the notion of patriotism. If patriotism means being blind to whatever the state has been doing to its citizens, then I contend patriotism is no longer a virtue because the state has lost its very ground to be defended. In this sense, the very meaning of patriotism is dissolved – it becomes nationalism.

As an extreme and damaging form of patriotic sentiment, nationalism has become a commonly used strategy of the Chinese government when it faces any accusations of human rights violations. Through repetitively appealing to nationalism, the Chinese government has rendered all human rights defenders, all conscious and righteous citizens with an aspiration for a brighter society, as a group of people who have an axe to grind and are often associated with anti-China forces overseas. To name a few, there’s Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate who called for Chinese political reforms and was incarcerated as a political prisoner; there’s Wang Yu, a human rights lawyer who defended women’s rights and religious freedom while being derided as an “arrogant woman” by Chinese mainstream media; and today there’s Yue Xin (she is roughly the same age as us), an outspoken #Metoo activist and recent graduate from Peking University who was secretly arrested by the police in Guangdong Province while participating in the labor movement in South China. These people were also running personal risks in defying their security-oriented government in pursuit of social justice and the universal attainment of human rights. And it has to be noted that they were doing it in a place where the very idea of human rights is perceived as a Western conspiracy and necessarily set at odds with Chinese nationalism.

True patriotism, on the contrary, requires civilian consciousness to identify what is just and unjust on the political level and what is righteous and unrighteous on the individual level. To love our country never means to conceal every negative (yet possibly authentic) portrayal of it; it never means to disregard the voice of the least advantaged, the oppressed, the “disappeared.” Patriotism never means closing our eyes and immersing ourselves in the nationalistic fantasy of paradise. In stark contrast, to truly love our country requires us to to love its people and defend their unquestioned and undeniable birthrights, regardless of which religious beliefs they hold. To love our country means to stand up against the dark and to fight for the breaking dawn, even though it might take efforts of one’s whole life to reach. To love our country means to take the initiative to make societal change in spite of personal concerns or fears, just as our contemporary Yue Xin has done.

It is my civilian duty, as a Chinese who loves their country, to put my reflections into words and make them public. Though I am aware that the presentation of the “truth” about Eastern developing countries in a Western context may not provoke positive understanding across cultures, I still want to reiterate a platitude here: that human rights matter for the sake of each individual, regardless of where he/she is from. I am, by no means, suggesting that the importance of Chinese national dignity is outweighed by that of a Western concept. Rather, through the attempt to demarcate Chinese government as a political entity and the Chinese people as a group who share the same land and ancestry, I am trying to negotiate between our national dignity and individual rights. Instead of either blindly supporting the film (which might reinforce Americans’ stigmas about China) or simply calling for it not to be screened (which might take away chances for Chinese people to learn about the certain issues in China) I am calling for us to establish a public space, for Chinese and American students, that permits plural political voices as well as multilateral discussions.

*Editor’s note: the author of this piece has been granted anonymity to protect them from any legal trouble they could face as a Chinese citizen defending the Falungong.