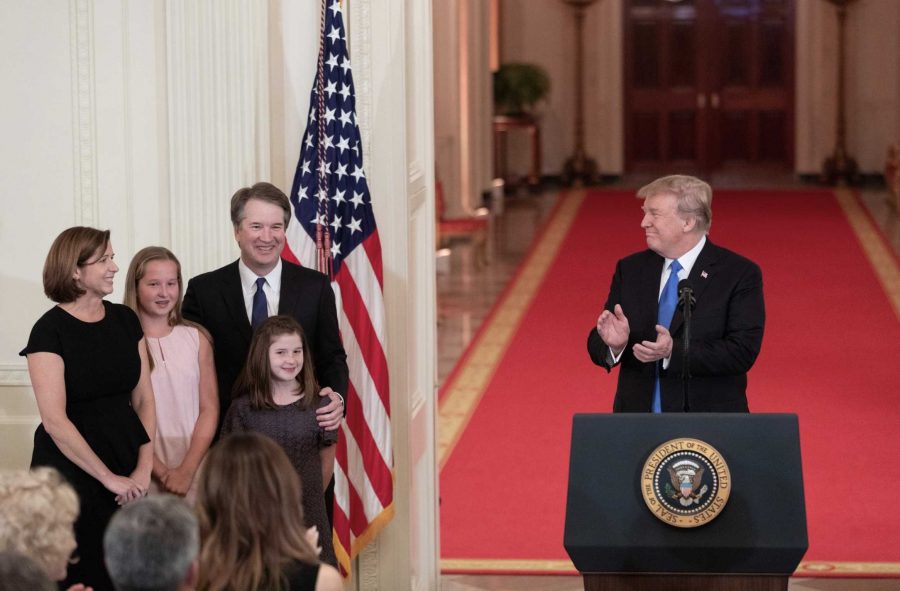

Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed to be the next Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on Saturday, Oct. 6. He was sworn in later that day, and assumed the bench the following Monday.

For conservatives and supporters of President Trump, the successful confirmation was an end to an ordeal and a powerful addition to Trump’s legacy. Others viewed it far differently, dismayed by the failure of the sexual assault allegations against Kavanaugh to prevent him from assuming the bench. For them, the 50-48 vote to confirm Kavanaugh didn’t just mark a definitive conservative shift in the ideological bent of the Supreme Court: it represented a blatant disregard for an issue raised by so many women in recent months.

Many also viewed Kavanaugh’s emotional reaction to the accusations as disqualifying for a Supreme Court justice. During the hearing, Kavanaugh refused to answer certain questions from Democratic senators, even asking Senator Amy Klobuchar the same question she had asked him. This temperamental criticism was reflected in a letter signed by over 2,400 law professors in the United States, including 10 from Vanderbilt Law School, in which they urged the United States Senate to vote against Kavanaugh’s confirmation given his lack of “impartiality and judicial temperament.”

Unfortunately, these law professors seem to make the mistake of extending Kavanaugh’s appearance in a Senate hearing to his habits in the courtroom, even though the Senate and a courtroom are completely different bodies. That Kavanaugh was unhappy with the proceedings may not have been conducive to an amicable hearing, but his dismay wasn’t unfounded. The allegations against him were at the time, as they are today, unproven, and he had endured a tremendous deal of scrutiny and public ire without any recourse to defend himself.

Even after the hearing, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations are unproven. An F.B.I. investigation prior to the confirmation vote yielded no corroboration to Ford’s story. Ford failed to provide any eyewitnesses who could directly verify her story.

Investigations into two other allegations against Kavanaugh–an alleged sexual encounter with Deborah Ramirez at Yale and predatory behavior at parties described by Julie Swetnick–also failed to turn up any corroborating evidence. The New York Times reached out to several dozen classmates of Ramirez, but no one with firsthand evidence could be found. The Wall Street Journal similarly investigated the Swetnick allegations, but the same result occurred.

I would sympathize more with the Vanderbilt law professors if their logic was purely based on Kavanaugh’s temperament. But several of the Vanderbilt professors went farther and claimed that Kavanaugh acted dishonestly. When speaking with the Vanderbilt Hustler for a recent article, Professor Alex Hurder said that Kavanaugh “did not have the character, or the honesty, required to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court.” In the same article, Professor Daniel Sharfstein found Kavanaugh’s testimony to be “full of readily provable un-truths.”

To suggest that anything less than the highest standards of justice should be used in the process goes against what our legal system is meant to support

It’s ironic that law professors and supposedly objective Senate Judiciary Committee members are so quick to jump to conclusions about a man’s testimony and automatically believe Ford’s accusations, when the presumption of innocent until proven guilty is the hallmark of American law. How can someone possibly point to “readily provable un-truths” said by a man under oath without having tangible evidence that contradicts him?

Some, like the Hustler editorial board, argue that “Kavanaugh’s confirmation process is really just a job interview for a court seat,” such that the innocent until proven guilty principle need not apply to Kavanaugh. A lower threshold, then, is perfectly suitable. But this isn’t simply a “job interview for a court seat.” This is an evaluation of a man being put up for the most important judicial body in the United States. To suggest that anything less than the highest standards of justice should be used in the process goes against what our legal system is meant to support.

The law professors also criticized Kavanaugh’s polarizing testimony. Sharfstein objected to Kavanaugh’s “sharp partisan tone,” and one of Sharfstein’s colleagues, Professor G.S. Hans, said that “some of the rhetoric went against” the expectation of non-partisanship among Supreme Court judges. And yes, some of what Kavanaugh said – particularly his allusion to a conspiracy by the Democrats and the Clintons against him – was clearly partisan. But imagine a scenario where your entire life’s work and legacy has been jeopardized by one person’s claims against you, grounded in an unverified, decades-old story that is nevertheless given the presumption of truth by legal scholars trained to evaluate claims objectively. With so much on the line and so little discretion being used to evaluate him, I think Kavanaugh had a right to be angry.

The real partisanship in this hearing came from those who chose ideology over truth. I’m not talking about Senate Republicans, who invited Ford to testify, gave her the chance to bring additional witnesses and respected the need for an impartial F.B.I. investigation (which ran to completion). I’m referring to opponents of Kavanaugh whose fright at the thought of a conservative Supreme Court compelled them to place more belief in an unsubstantiated, thirty-year-old story told by one woman than in the testimony under oath of a man who, like all others in this country, deserves no less than the presumption of innocence. Anything less is antithetical to the legal foundations of our country.

I’d like to think that academics and professors, especially at my own school, are above the partisanship that has weakened our political system. But when professors put faith in an unverified version of the facts, as if the truth can be molded to one’s political convenience, we abandon our country’s traditions and let emotional politics reign supreme over due process, humility and justice.