Thirty one percent of sexual assault survivors choose to report the incident to law enforcement. That number is even lower on college campuses–only 20 percent of female student victims choose to report incidents of sexual assault, according to the Department of Justice. Cara Tuttle Bell, the director of the Project Safe Center for Sexual Misconduct Prevention and Response, believes that if police implemented new methods for how they approach communication with sexual assault survivors, then fewer sexual assaults would go unreported.

Tuttle Bell is a proponent of Forensic Experiential Trauma Interview (FETI) training, which provides police officers with techniques that help them build rapport with, ask questions to and gather information from those who have experienced sexual assault, according to End Violence Against Women International, which specifies that the training is a step towards creating a trauma-informed approach. Tuttle Bell hopes to capitalize on the “strong, well-established” relationship between the Vanderbilt University Police Department and Project Safe to implement FETI training for all VUPD officers going forward.

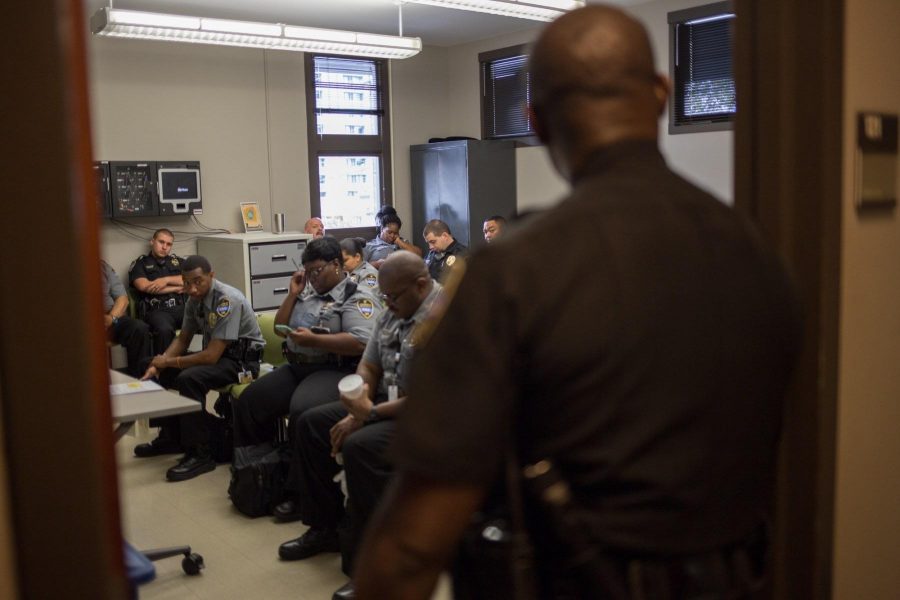

Five of the six VUPD criminal investigators went through FETI training last September, and the sixth investigator, who was recently hired, will be going through the training soon, according to VUPD Assistant Chief Rick Burr. Burr is communicating with the VUPD training committee about the possibility of implementing FETI training into the annual training for all VUPD officers in future years.

“We recognized about a decade ago [the concept of] re-victimizing individuals who have been through traumatic events, and we have policies and procedures in place where the responding officer knows to get very little and limited information,” Burr said.

When VUPD receives a report that a sexual assault has occurred, a responding officer arrives on the scene, whether that be at the Medical Center or another campus building, and collects just enough information to determine jurisdiction and whether there is a crime scene that needs to be preserved, according to Burr. The responding officer then notifies a Project Safe representative, the on-call VUPD detective, and the Metro Nashville Police detective, who all respond jointly to the scene. In most cases, the survivor will undergo one interview, which is usually led and conducted by the MNPD detective upon their arrival.

Metro Nashville Sex Crimes Unit detectives have not gone through FETI training, although the unit’s supervisor, Lieutenant Virginia Carrigan, is aware of the training and may implement it for detectives in the future, according to Don Aaron, a spokesperson for Metro Nashville Police.

“Sex Crimes Unit detectives know very well the impact that emotional trauma can have on victims and work these investigations in such a way that the well-being of victims is of paramount importance,” Aaron said.

Tuttle Bell believes that FETI training would be an asset to all VUPD officers, including those who ask minimal questions, and eventually to other campus players, as well.

“FETI training is beneficial for anyone responding to those who have been sexually assaulted,” she said. “I would encourage this training for all involved–Project Safe staff, Title IX staff, Housing and Residential Education staff, and all police departments nationwide.”

According to Tuttle Bell, the training goes beyond an explanation of fight or flight responses, which are well understood, and explains reactions such as freezing, appeasing and being unable to recall events in chronological order after a traumatic event such as sexual assault. Furthermore, the training improves responders’ ability to approach victims of crimes committed by an acquaintance, a common occurrence on college campuses.

“The training helps reframe the way people tend to think about sexual assault and help those who collect information from victims of these crimes to understand why those who have been assaulted might be presenting the way they do,” Tuttle Bell said.

The FETI approach was designed by law enforcement for law enforcement, and is based on and informed by medical research. Aspects of the training may seem counterintuitive to officers at first, Tuttle Bell said.

“Our very well-meaning, sometimes life-risking campus partners want to put a stop to the harm, reduce others’ risk, and hold people accountable,” Tuttle Bell said. “That’s a shared goal. So, if we take what we know about how the body reacts to trauma and let that inform our approach to working with the victims of these particular crimes, then we produce less victim-blaming or shaming experiences.”

Burr is a supporter of the training and believes all law enforcement officers can benefit from understanding how individuals respond to trauma, although he has not gone through the training yet himself.

“If it were up to me, every law enforcement officer would take FETI training,” Burr said. “It’s a relatively short class, it was inexpensive to obtain, and even if our police officers aren’t the ones actually doing the interviews, I think it speaks to patience and understanding. If a trauma survivor doesn’t remember all the specific details of a crime, to not be so quick to assume they are not being forthcoming or honest. I think that happens in a lot of cases, and that could potentially be a situation where even officers who aren’t involved in those interviews take something away from it.”

Implementation of widespread FETI training is far from the sole agenda item Project Safe is pursuing this year. Amid increased conversation about sexual harassment and power based personal violence in light of movements such as #MeToo, Project Safe has seen an increase in requests for programming on topics such as workplace conditions and relationships, Tuttle Bell said. The center is also looking to expand programming aimed at graduate and professional students and to build up a presence among postdoctoral scholars.

“Prevention is possible. New norms are possible. So, the work continues,” Tuttle Bell said.