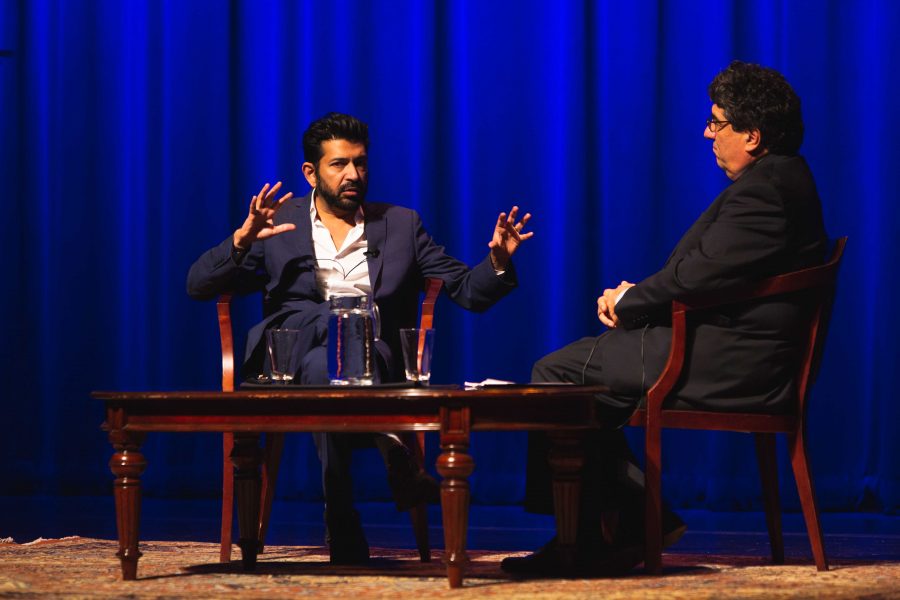

Patrick J. Kennedy came this past Tuesday for the Chancellor’s Lecture with Chancellor Zeppos. Kennedy is a past U.S. Representative from Rhode Island’s District 1 and currently advocates for mental health and drug abuse legislation that better accommodates Americans. Kennedy’s major bill was the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and he’s spent most of his spent time since leaving Congress trying to get it enforced.

Vanderbilt Hustler: What was it like holding an office while you were in college? Do you think it’s possible for students to do that now?

Patrick Kennedy: In my case, Rhode Island – small, small state, smallest in the country – we had a huge legislature, not as big as New Hampshire, but I could literally walk my whole district. And the reason I got that idea is that I had interned at the State House and I literally went and got a map of where I lived and saw the district confines, I knew all the streets, and I went about getting the voter lists. But the point is that, when I was in the State House, I looked at these reps, and I said to myself: I can do this. And that’s the way I hope lots of young people could feel if they were involved and saw this mysterious thing called politics up close. I think that a lot of them would say, wait a second, why am I giving this to someone else to do. I want to have a say in the way the world is orchestrated.

VH: You have a special position in that you’ve been involved in both politics and advocacy groups. What are the limitations and freedoms of both of those roles?

PK: I would not be able to an effective advocate today had I not spent 22 years in public life. I’m pretty much right up there with everyone else who says that our system is broken today, and you pretty much can do nothing. I mean, when all they’re doing is passing these continuing resolutions and there’s no regular action on any piece of legislation. It’s a fundamental breakdown in congress. I’m glad that I’m not having to be in congress today and having to suffer the indignity of being there but not having my voice heard on behalf of my constituents. I think it would be really frustrating as I know it is for my cousin Joe. When I was there you actually could pass things and get things done.

VH: What do you think has changed?

PK: So when I first got elected it was the year Newt Gingrich became Speaker of the House, and he started, or accelerated if you will, this drumbeat of, everybody in government is corrupt, they’re all to blame for all your problems. Some House of Cards stuff, you know, cynical, cynical, cynical. And then we moved from a real majority-rule system to a parliamentary system. Now, in a majority rule, it’s both parties. Whoever’s the majority, based upon votes they can get from both parties, that’s who wins the day. In a parliamentary system, it’s only one party passing bills. And if that party can’t pass a bill will its own members alone, then they don’t bring up anything that could be passed with some of their members, but with a lot of the members of the opposing party. That’s now something that’s like, you can’t imagine that those days actually existed until the beginning where Newt Gingrich was like, we’re not going to take Democrats’ input, it’s just a Republican agenda. And now that’s kind of moved over to the Senate, because so many of the House members in the Gingrich Revolution became Senators, and now Senator McConnell basically operates the same way. And Harry Reid ended up having to do the same thing because he saw that as the new way, and unfortunately that is not the way the founders of our country designed either the House or the Senate, especially the Senate. The Senate was definitely supposed to be someplace where you voted your conscious, not your party. That was definitely the way the Senate was supposed to be set up. But today, it’s really… it’s sad.

VH: So what would you say you have been able to do in your foundations like One Mind and The Kennedy Forum that you haven’t been able to do in politics?

PK: In the private sector it’s a campaign. The way I’m using it, I’m taking all of my political campaign experience, but applying it in the private sector. So I get people who want to be a part of it because it’s in their direct financial interest. I’ve got people who want to be a part of it because they have a personal story and they’re connected and they want to do it purely altruistically for philanthropic reasons. You’re not as precluded as to who you can involve. You can involve a whole host of folks. So there’s a lot more flexibility in terms of advocacy that you have in the private sector.

VH: Do you think we’ve made strides in addressing the opioid epidemic the past decade?

PK: So we’ve only just started to do stuff. It’s really been slow, slow, slow. I say that we’ve got an inferno and we’re using a garden hose to try to put it out. We’re spending half a billion dollars a year, and that sounds like a lot of money. But we’re losing 64,000 Americans, and that’s conservative so it’s a whole lot higher than that. In the height of the AIDS crisis we were losing 53,000 Americans, and when we were faced with that crisis, Congress appropriated 24 billion dollars a year to tackle that crisis. And yet we’re losing more people and not even spending half a billion dollars. So all I can tell you is that the big enemy we have right now is ourselves and the prejudice and biases against the people who suffer from the disease of addiction. Because it’s still not understood, and even though intellectually we have a better understanding of addiction, societally we’re still not there yet in terms of embracing it as a public health issue. We still want to treat it as a criminal justice issue. And that’s what we’re doing, you know, our jails are filled with people with these issues.

VH: You talked about waiting until a crisis occurs before taking any action. Whenever we have a crisis with gun violence, we always hear people bringing up mental illness. What is your opinion on that? Are there things that we could do better with mental illness in regards to gun violence?

PK: Well, first, we don’t have any more of a percentage on a population basis in the United States of people with mental illness than any other country around the world. And we don’t have any less, on a per capita basis, number of mental health professionals. So why are we the only country in the world with these mass shootings? It’s got nothing to do with mental illness. It’s got to do with the availability of high powered assault rifles. The same people are walking around in Australia and it’s not happening. The same people are walking around in Great Britain and Germany and France and it’s not happening, and are walking around in Japan and it’s not happening. It’s not happening! So you can not say that this is a mental illness issue. Sure, people have mental illness, and sure, they get blamed, although truth be told, more often than not they’re victims of violence and not perpetrators. In some rare cases people with mental illness have a slightly higher predisposition to violence, but the majority of people who are doing this, they’re just bad people. I don’t know if this Cruz fellow was mentally ill, but he premeditated this! This was totally premeditated. Planned. Premeditated. And a characteristic of mental illness is when you have lack of insight. Tragically, if you are someone who suffers from mental illness you are so much to likely to be abused, victimized in all kinds of way, and ostracized of course.

VH: What are ways you think institutions like Vanderbilt can help better accommodate mental illness for students?

PK: I would say that given the stresses on young people today, and given the importance of having good mental health hygiene on campus especially among students, and given the need for them to understand the importance of their own mental health hygiene, it is absolutely essential that every professor in Vanderbilt, teaching assistant and the like, has to go through some type of training, if you will. It can be done in any number of ways, but they should not be too busy to know more about what their students are experiencing in their classrooms. Especially given the fact that so much of what we understand to be poor mental health is driven by stress, and certainly on a campus as highly challenging as this is in terms of its academic rigor, it’s important for professors to know their role in that stress, and also their role in helping their students manage that stress. Because what they’re trying to impart is a life lesson. It’s not just the subject matter that they’re imparting. It’s how does their student respond and learn. And part of that learning is the environment that they’re learning in. We can’t expect that the only students that get help are the ones that go over to the student recovery center. It’d be better if this was universalized. The vulnerable kids in their classrooms, they don’t even know who they are, and the vulnerable kids in the classroom are probably the least likely to want to go over to ask for help. So it’s a moral imperative. If you want one headline for your article, it’s: Congressman Kennedy challenges Vanderbilt faculty to learn more about the importance of what they can do to be facilitators of their students understanding how to manage stress, and the importance of doing that, and almost making that part of the expectation. We’re going to be tough on you, and we’re not going to let anyone off, but we want you to be sensible. When you have challenges, see me. I also expect you to, you know, here are thing you can do. And we’ll celebrate that. So this is something that should be part of the education that Vanderbilt offers. Not something for “those students.” It’s for everybody to be better. That’s the way to look at it.