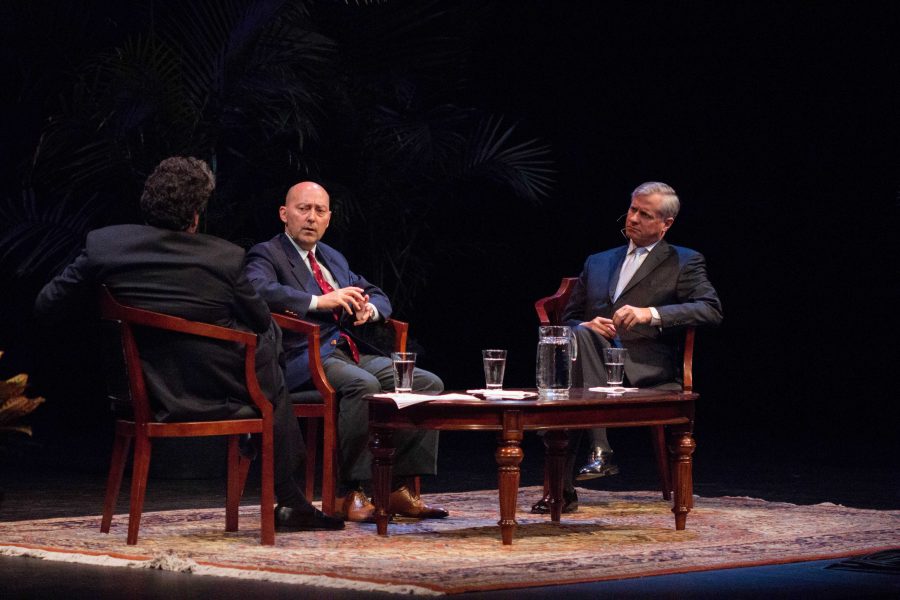

Admiral James Stavridis served in the United States Navy for 37 years and now works at Tufts University as the dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Admiral Stavridis was the 16th Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and has considerable experience with world security. On Tuesday, October 3, Chancellor Nicholas Zeppos and Vanderbilt Distinguished Visiting Professor Jon Meacham sat down with the Admiral to discuss his perspective on world security and how the U.S. plays a role in confronting international challenges.

Vanderbilt Hustler: You were talked about as a potential candidate for both the Clinton Administration as well as the Trump administration, proving that you have bipartisan respect. How do you feel about working as a dean at Tufts, and do you believe that you will return to a different or more active government role?

Admiral Stavridis: I was one of six who were vetted seriously for Vice President with Secretary Clinton. If she had won, I was prepared to go into government with her perhaps as the National Security Advisor. The Trump team also called me, asking if I would interview with then President-elect Trump. I did the interview and decided that I would not be a good fit in his administration for policy differences. I think that I have been looked at across the political spectrum principally because of my military background. There is correctly a view that the U.S. military is nonpolitical, that the U.S. military wants what’s right for the country. I’ve had a life of service, and if called upon in an administration that aligns with my policy views, yes, I could certainly see myself doing that. I will add that I am enjoying myself immensely as a dean. The thing I loved most about the Navy was mentoring young people, and I find that as a dean, you’re still close enough to students to have that experience. I’m quite content where I am, but I’m willing to serve.

From the moment I got onto the deep ocean out of sight of land, I knew I wanted to be a sailor

VH: Can you share a little bit about your influences in life and what called you to serving our nation in various capacities?

ADM: For me, it was easy because I grew up in a military family. Graduates of the Naval Academy can either join the Marine Corps or the Navy, so I went to Annapolis convinced I was going to be a Marine because I was following my father’s example. He served his country in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. I got to Annapolis and was sent out to sea on a cruiser, a big beautiful warship, out of San Diego. From the moment I got onto the deep ocean out of sight of land, I knew I wanted to be a sailor. I merged my idea of military service with a love of the ocean and a love of being a sailor, and that’s what led me to public service.

We can best put America first by working with our allies, partners and friends

VH: You have stated, “Instead of building walls to create security, we need to build bridges.” How can we build bridges in our relationship with our allies? Do you think that the U.S. still has the same respect and stature globally that we have had with previous administrations?

ADM: If you look at the history of our country, we do better when we try and build bridges. Perhaps the most dramatic, negative example of this is with the U.S. in WWI. By 1919, the world is trying to rebuild itself around this idea of the League of Nations, a forerunner of the United Nations. Through a long series of domestic political disagreements, the U.S. rejects the idea of the League of Nations, pursues an isolationist strategy coming back to America and erects walls called “tariff barriers.” How’d the war in Europe turn out? We cracked the global economy. That led to the rise of fascism, and we stumbled into a Second World War, three times as bad in terms of casualties as the First World War. Learning from that experience, the U.S. came out of the Second World War, correctly built bridges and helped build international bridges. These are the international organizations that we esteem today—the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, etc. We have done pretty well by those institutions, both as a nation and as a world. By almost any metric looking at that post-World War II period, we’ve seen improvement and advancement. Granted, there are pockets of pain in many countries. There’s still big poverty in Africa and Latin America. Here in the U.S., we have pockets of our society that we have not pulled along as we should have. But broadly, those institutions and that philosophy of building bridges have served us quite well. This is the root of my disagreement with the Trump administration. It’s this idea of blindly putting America first. Now, we always want to put our own nation first, but we can best put America first by working with our allies, partners and friends, by building bridges even to our opponents.

VH: Do you believe the issues that drive American interests continue to be the same? Do they transcend time no matter who is in power, or do you believe the paradigm in American policy has shifted substantially under Trump’s administration?

ADM: I think that our national goals in the world are actually straightforward and consistent. We want to have a value-driven nation that esteems democracy, liberty, freedom of speech, freedom of expression, freedom of education, freedom of assembly—the things that are enshrined in our founding documents. Those are the right values. We execute them imperfectly, but they’re the right values. That’s Number 1. Number 2, we want a prosperous nation. We want an economy that works. We want people who do not live in poverty. We don’t want hunger in America. Number 3, we want security. We want to avoid conflict wherever we can. We should confront when we must but cooperate where we can. That means creating security, not only through our own military strength, which is important, but also through our alliances, our partnerships and our network of friends throughout the world. All of that is additive to creating security. Fourth, and this one is new, I think our nation needs to be a leader in the cyber world because it has become so interwoven with the fabric of our lives. We need a more secure cyber engagement policy for the nation because it underlies a great deal of our economy. It’s the newest of the imperatives for our nation. Now, how you do achieve these goals? That goes back to question 3 that we just answered. We should you try and achieve them by building real alliances, connections and friendships.

The military is very good at launching missiles. We can also launch angels from the sea.

VH: What do you think the U.S. military’s role is in helping Puerto Rico and addressing issues of human suffering?

ADM: Before I was the NATO Commander, I spent three years as the Commander of U.S. Southern Command, which is in charge of all the military activity South of the U.S., so I’ve spent a great deal of time dealing with natural disasters. The military’s very good at launching missiles. We can also launch angels from the sea. We have logistic muscle that’s extraordinary. When you look at what’s happening in Puerto Rico today, eighty percent of that response is from the armed forces, the National Guard of Puerto Rico, the State Guard from other states in the U.S. and the active duty military. We have several amphibious ships, and we’ve got a hospital ship there. The military has a fundamental role in these kinds of soft power operations. That capability has been on display in Texas after Harvey, in Florida after Irma, and in Puerto Rico after Maria. I must observe that the military reacted very quickly to the first two, but I think we’re playing catch-up ball in Puerto Rico, and that troubles me.

VH: Part of your life’s experience involves defending our nation as a result of our military power and resolve. How can we as a nation use that same resolve to protect our citizens from the rampant and brutal statistics we have due to gun violence, especially in light of the massacre in Las Vegas?

ADM: Well, the first job would be to get a functioning gun control regime in this country, starting with banning assault weapons. I’ve spent my life around very high-powered weapons. There is absolutely no reason that American civilians ought to have access to weapons like that. I do support the right to bear arms for rational purposes to include hunting and self-defense, but none of that requires the kind of lethality that we saw on display. How many times do we have to see this? We see children massacred at Sandy Hook. We see Pulse Nightclub ripped apart with 54 dead in Orlando. Now, we see this horrific event in Las Vegas. I can only hope that our leadership stands up. So, arms control is Number 1. Number 2, more philosophically, I think we need a culture that respects others, that inculcates from the very earliest stages in people’s lives that people need to cooperate and work together. In the U.S. we do quite well in higher education, but we have much work to do in primary and secondary education. Thirdly, we have to collectively try and tamp down what some are beginning to call the “anger industry,” which is the national media operating on the fringes of political activity. This tone of violence and intolerance has increased over the last decade. It’s not simply a function of the Trump administration, but I do think the Trump administration has contributed to an up spike in that kind of intolerance. He needs to tamp down his rhetoric in significant ways and be an example. Those three things collectively are all important, particularly education. By the way, can I recommend a book? It’s called “Rules of Civility.” It’s a short and very practical book about tolerance. You would think that many of our leaders would have read it given that Washington was our first President. You don’t see a lot of civility these days from our leaders. We need leaders who can be more balanced, centrist and tolerant and can have a sense of humor. That would help a lot.

People say to me a lot “thank you for your service.” I would say to every student, “I hope in ten years I’ll be able to thank you for your service as a teacher, as a volunteer, as a peace corps, as a military person, as a diplomat representing the country.”

VH: In spite of everything happening, how do you keep hope, and how can youth be inspired to make change by leadership that lacks such civility?

ADM: We have challenges and many things that ought to worry us deeply about our society today, yet let’s keep a perspective on the long throw of history. A hundred years ago, African Americans effectively still lived in bondage in this country. Women could not vote or hold significant jobs. Immigrants were extremely prejudiced against. We were heading into a global depression, and we were in a passage that would lead us through a world war in which sixty million people would die globally. We’re not there. We have a lot of challenges, but we’ve made incredible progress on so many different fronts, so the first point is to recognize that the long throw of history is on the side of light. Martin Luther King said, “arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” It’s not a sudden curve, but it’s bending in the right direction. Number 2 is that technology, although it has down sides and creates hard choices for us, is helping us. It’s creating more transparency. It’s creating efficiencies in our lives. On the biological side, it’s extending our life. It’s improving our performance as human beings. There’s great hope in that. Third, while it’s hard to find national leaders who are examples of brilliant public servants, I would argue to look around at people who are quietly serving in this country. I was in the military for thirty-seven years, and people often say to me “thank you for your service,” but it’s not just the military. There are so many ways to serve this country—our police, our firemen, our first responders, our teachers, our Peace Corps volunteers, Volunteer for America, AmeriCorps, our journalists, who often risk their lives to uncover facts. We tend to look at the most senior politicians, but what about the people on the county water commission or the Vice Mayor of a small town or the chairman of the school board? They are typically not paid and are serving in that way. I would tell young people to look around at these examples of quiet service. That’s before we even get to charitable acts, like soup kitchens, things that you watched your parents do and that students do very well, so I’d say there are some very positive aspects to the society around us. The pitch I want to make to students is to find a way to serve. Again, people say to me a lot “thank you for your service.” I would say to every student, “I hope in ten years I’ll be able to thank you for your service as a teacher, as a volunteer, as a peace corps, as a military person, as a diplomat representing the country.” There are a lot of ways to serve, and you can do it for an afternoon, or a month, or year or a whole career, but find some time for service.

Quotes edited for length and clarity

Photos by Emily Goncalves // The Vanderbilt Hustler