We’ve all heard horror stories regarding the treatment of women in big tech giants like Google and Amazon, seen statistics pointing to the clear imbalance of women in STEM fields, or noticed a difference in the number of girls in a STEM course. Frankly, there’s been a ton of initiatives to get more women in STEM, and while that’s terrific, I don’t think any of them will truly succeed if we don’t make one change: to stop ignoring one side of the equation. Instead of focusing on the plentiful initiatives available to bolster the presence of women in STEM fields, attention must be paid to the countless emotional hurdles facing women who bravely take advantage of these opportunities.

I graduated high school a few months ago and perhaps one of the most formative moments in my high school career was an end-of-the-year challenge we were given in my AP Physics C class. Initially, I didn’t think much of the fact that the class was heavily dominated by boys, as I figured that surely, gender bias in a high school classroom in 2017 was just an outlandish idea. I was wrong, to say at the least.

The challenge given to us by our teacher was to form a group, build a catapult, and then use it to shoot a marble at a stuffed monkey about 15 yards away. My group was the only group that was made up of all girls. When we asked our physics teacher for a screwdriver, one boy acted as if we couldn’t possibly know what a Phillips head screwdriver was, much less use it. This was an incredibly ironic moment, as two of us have been on a robotics team for four years and had thus had ample experience with screwdrivers and how to use one.

When we were the only group that managed to hit the stuffed monkey with our catapult, several of the boys–watching from 15 yards away–disputed it passionately, declaring that the marble didn’t actually hit the monkey. This was despite the fact that we all heard the sound of the marble making contact with monkey and the fact that our physics teacher, standing a foot away from the monkey, said it hit.

Instead of accepting that the marble had hit and that they’d been bested by a group of girls, the boys demanded that we go again to “really prove” it hit, and then proceeded to obnoxiously crowd around the monkey with their jeers, starting to film the shot just to ensure we couldn’t cheat.

Throughout this experience, my groupmates and I could only feel shock at what could only be categorized as blatant sexism–because of course, a girl couldn’t be good at building. It was especially disheartening considering the fact that all three of us planned to major in engineering.

Really, this situation was an incredibly apt metaphor for how women have to work twice as hard and be twice as good in order to receive the same credit and respect they would have received had they been male. We all knew that if an all-boy group had won the challenge, they would have been congratulated by the class, never expected to replicate the shot and have their integrity called into question. We all knew that had we been male, we never would have heard comments about how we only got into a school or gotten an opportunity just because of our gender. What really demoralized us, however, was the knowledge that it wouldn’t get easier onwards in life–that what we had experienced was practically nothing compared to what other women have experienced in STEM careers, that it wouldn’t get better until a fundamental change occurs in society.

While it was an accomplishment in and of itself that my group was composed of all girls and that we had all decided to take this incredibly challenging STEM class, I felt as though I wasn’t welcome there. No one directly said anything remotely similar to me not belonging or not being capable, but that didn’t stop me from feeling like I didn’t belong or that they thought I wasn’t capable. This encompasses the fact that even though women aren’t blatantly told that STEM isn’t the major or career for them, and are actually actively encouraged to pursue these majors and careers, they still feel isolated and awkward in fields that are still largely dominated by men.

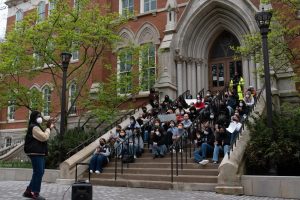

While solving this issue isn’t extraordinarily straightforward, steps that takes into account the other side of the equation can be taken to improve the status quo. First of all, people need to learn how to treat women as equals in research and academic environments. Similar to the Alcohol Edu course all Vanderbilt first-years are required to take before classes begin, a similar course could be implemented presenting existing statistics regarding women in STEM, what a gender-based bias in the workforce or lab would look like, and provide resources for where women can report instances of gender-based bias. But instead of only being geared towards first-years, the course could be available, or even required, university-wide.

But that still isn’t enough. Until women are placed in leadership positions across STEM, there will not be a model for other women looking to succeed and move up in the field. To help women achieve this upward mobility, universities could create workshops uniquely for women to discuss how to overcome the barriers they face along their upward path. Having a mechanism for discussing emotional challenges surrounding the workplace environment could increase resilience of women in the field by giving them a community of support and a forum for airing their grievances.

Department heads and STEM managers need to go out of their way to make sure that women are receiving equal treatment and opportunities. Several studies have shown the fact that women are underrepresented in research facilities despite producing higher quality research on average. MIT’s Study on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT revealed “unequal distribution of resources between male and female faculty in every variable that was measured: lab space, salaries, proportion of funding from the Institute, and nominations for prizes,” as well as exclusion of women from important decision-making. However, the study found that women were still expected to complete extra responsibilities–like a heavier teaching load. Later studies completed in other universities across the country told a similar tale.

In conclusion, no amount of STEM initiatives will get women to stay in STEM if what they experience in classrooms, research facilities, and boardrooms is thinly-veiled or blatant sexism. If society still has an archetype for what a successful person in STEM looks like (read: male), ridiculing or ignoring women trying to enter and stay in STEM, nothing will change. Girls will give up on STEM– not for a lack of interest, but because of the heavy opposition they face as well as the lack of recognition and credit they experience. Just like how sexual assault cannot be prevented just by giving the victim tips on how not to be assaulted but by also changing the rape culture prevalent in society, this lack of girls in STEM cannot be fixed before society has caught up too: before this culture of female inferiority is changed.

Until then, every effort will be for naught.

Stephanie Wang is a first-year in the School of Engineering. She can be reached at [email protected].