The lights dim. An electric anxiety surges through the audience. I realize I may have waited all my life for this. Meanwhile, the piano sits center stage: plain, unremarkable. Suddenly, a shattering applause ensues, one second too early before a young man, equally unassuming, enters my line of sight. The anxiety reaches its peak. I realize he’s slimmer in real life. After bowing cursorily, he sits down on the bench and rests his fingers on the keys—the world is still. Then, like a magician harnessing his equipment, purposeless and static without his touch, he strikes the first chord, and the silent instrument comes to life.

Two years before his Seoul concert (whose tickets were sold out in nine minutes), Seong-Jin Cho won the International Chopin Piano Competition, one of the four most prestigious piano competitions in the world. Though the honor is by no means small, especially as he is the first South Korean to win first place, his victory came as little surprise. His lyrical style, coupled with his ample use of the pedal, perfectly captured the bittersweet nostalgia of Chopin’s work. Cho’s technique was refreshing because he paid special attention to the slower and gentler phrases, normally glossed over by musicians and listeners alike, and endowed them with pure, almost angelic voice. Thus the performance’s emotional power lay not in force or heaviness, but rather in the softest tones in which Seong-jin, sensibly, drew back, and it was as if the keys were breathless.

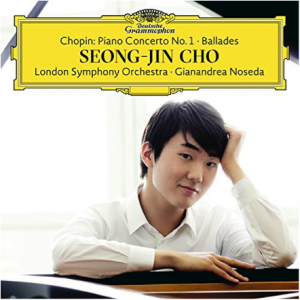

Cho’s new studio album shows how much his style has matured since the competition. While his previous renditions dwelt on exalting the lyricism and beauty of a piece, they now focus on a broader range of emotions. In the first Ballade, for instance, the pianist shatters the composition’s pensive depth by concluding in an almost hysterical cackle of notes. And throughout the ballade, he imbues the fast lower notes with a kind of dark charisma, only to quickly transition to an agitated striking of high keys that almost sounds like a cry for help. But this doesn’t mean that the first ballade is not without its lyricism; the first variation of the second theme is particularly lovely, and its subsequent variations feel grandly romantic.

Undoubtedly, however, the third Ballade is the most romantic and lyrical of the four. A gentle, meandering introduction quickly gives way to a regal waltz-like interval, evoking reflective pride, a unique emotion that seems to pervade Chopin’s work. Soon, the piece’s sweet main theme matures into a deep forte, which seems to express ardent dedication. Interweaved within these melodies are four pairs of mellow notes (perfect octaves of C) like a bird’s call, which always presage a recurrence of the pure main theme. Slowly, however, an anxiety begins to underlie the melodies, growing until it eventually explodes in a dazzling firework of musical color, whose energy fuses with the notes and impels them forward, creating a tension that is never quite released, not even in the emotional burst at the Ballade’s conclusion. It’s not Cho’s first time funneling the energy from a section to create unreleased tension. His interpretation of Ravel’s La Valse exemplifies his technique.

Ballade No. 4, as my personal favorite, is oddly enough also the most difficult to describe. Roughly put, it is a microcosm. As the longest, most progressive, and most intricate of the Ballades, its character cannot be concretely pinned down like the other three; it has multiple characters, varied moods that surge and weave as it progresses, constantly defying a single definition. The result is not a cohesive emotion or atmosphere evoked, but rather a vague outline of something in the distance, a mere sense of the immense and beautiful, as if the entire Ballade were a profound description of a personality rather than a personality itself. That’s not to say it’s somehow emotionally obscure or distant; a highly visceral reaction is evoked, if not more so, in this Ballade.

Cho’s role, of course, cannot be overemphasized. He has long had the ability to critically capture the hidden, implicit melodies of the most experimental of pieces, that is, to “read between the notes,” making them accessible and emotionally immediate. In the fourth Ballade, he does not simply alternate between minor and major key, but rather makes the major key phrases surge from the minor key, like a flower rapidly blooming in the dust. Later, he adds depth to a seemingly shallow flourish of high notes, evoking the image of a finger gently skimming the water’s surface while splashing a few drops along the way. Most significantly, however, his rendition of the Ballade’s climax is exquisite, powerful . . . and truly indescribable. Words, I believe, would impinge upon the sheer impact of this section; it would better suspend in verbal silence. Let the music speak for itself.

webbanki