Before college, I once had a teacher who told stories about how she had wanted to become a teacher ever since the age of three. She would describe how she came from a family of educators, how she played “school” with her siblings as a little girl, and how the drive to teach had motivated her throughout her life. She would then tell her class how much she enjoyed her job, with the goal of encouraging my classmates and I to pursue whatever dream represented our personal equivalents of her love for teaching. The story ultimately boiled down to a piece of advice that we’ve all heard before: “Follow your passion.”

I remember listening to her as a younger student and trying but failing to relate to her example. In comparison to her narrative, my life seemed devoid of any obvious or all-consuming “passion.” In contrast to the consistency of my teacher’s life goal, my career goals had transformed countless times since the days of my three-year-old self, back when I wanted to be a professional ballerina for the rest of my life. (This was before I realized that doing ballet requires physical strength, flexibility and grace, all of which I’ve lacked for 19 years and counting.) Of course, there were certain subjects in school and certain extracurriculars that I enjoyed more than others, but I didn’t consider any one of my activities to be far more worthwhile than all of my other involvements.

Today, I am a pre-med student, but my interest in pursuing medicine primarily comes from my experiences with shadowing physicians and doing service in healthcare settings, rather than some lifelong inspiration that has driven me since childhood. I don’t mean to imply that I doubt that some individuals can have childhood dreams that stick with them throughout their lives. In fact, I fully believe in my former teacher’s sincerity and the truth of her story, as well as the stories of similar individuals who also found their calling early in life. However, my personal experience tells me that there are plenty of adults of all ages who feel as though they still can’t pinpoint something and say with certainty: “This is my passion, and this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.” As for me, even though I’ve decided to pursue the pre-med track, and even though medicine appeals to my love for both science and service, I still don’t feel completely ready to label medicine as my “passion” — especially since I’ve never practiced it and am still years away from being licensed to do so.

What I wish my former teacher had included in her advice is that passion doesn’t arise instantaneously; instead, it’s something that must be grown and cultivated over time. When Humans of New York (HONY) founder Brandon Stanton arrived on campus a few weeks ago, his passion for working with HONY was obvious to everyone in the audience. But there were also plenty of twists and turns in his life prior to founding HONY. Before starting his now-famous blog and Facebook page, Stanton worked as a bond trader in Chicago, and only took photographs as a pastime. His passion for developing Humans of New York grew from what originally resembled nothing more than a photography hobby and a budding desire to interact with unfamiliar people. Stanton hadn’t been a lifelong photography and interviewing expert before he started HONY; he simply put in the time and commitment necessary to transform his interest in taking photos and making personal connections into the passion that has impacted the millions of HONY followers and contributors today.

Thus, in general, perhaps we should worry less about “follow our passions” and instead think more about following our interests, and giving those interests an opportunity to develop into passions. This is especially relevant to us as Vanderbilt students, because we often pressure ourselves into perceiving our eventual graduation as a deadline. We tell ourselves that by that time, we’ll need to have figured out exactly what our “passions” are so we can plan out the rest of our lives. But perhaps what we should actually be doing is not to fully commit ourselves to any single path, but rather to keep an open mind about the developing potential of the activities and academic interests with which we are already engaged. Even a not-quite-perfect career choice (like Stanton’s temporary job as a bond trader) can turn into a learning experience that ultimately helps us find the role that we want to play in contributing to our communities. And when we finally discover that role, we’ll know that that achievement would have been impossible without the journey we took to making that discovery.

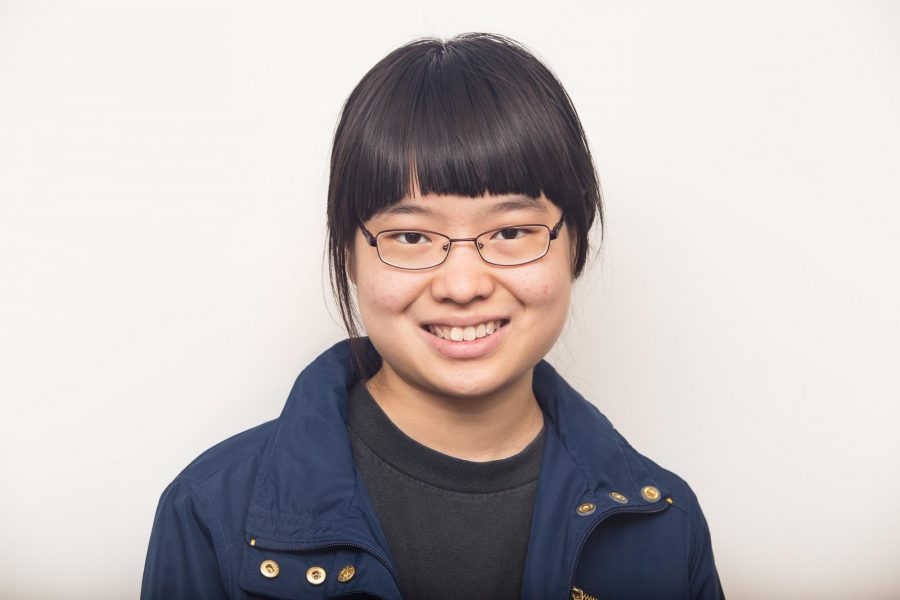

Alice Li is a sophomore in the College of Arts and Science. She can be reached at alice.y.li@vanderbilt.edu.