This year, journeys to class have begun to look a little different. Building upon this spring’s successful pilot of dockless Ofo bikes, motorized dockless scooters came to campus earlier this fall.

Lime and Bird scooters began popping up around Vanderbilt this fall following Metro Nashville’s establishment of a one-year pilot with the companies. Vanderbilt signed an agreement with Bird and Lime to allow their devices on campus beginning Sept. 6, provided they abide by Vanderbilt’s safety and etiquette guidelines.

Now, students can’t go anywhere without seeing a scooter parked at a bike rack, planted in the middle of a sidewalk or zooming by them at up to 14.8 miles per hour, according to Lime’s website. These scooters work just like Ofo bikes: students must download the respective Lime or Bird app, connect a payment method, agree to terms of use and then unlock the scooters by pointing their phone camera at the scooter’s QR code before riding the scooters for $1 flat rate and 15 cents per minute.

Ofo told Vanderbilt administration on Oct. 11 of their decision to leave both Vanderbilt and Nashville, stating that they would be removing bikes in the following weeks. The company pulled out of a number of major cities this summer, citing regulatory difficulties with various cities. Ofo’s pilot began on March 27 with plans to operate on campus for six months, so Ofo is loosely sticking to their initial plan.

“While this is sad news, the pilot with Ofo was very beneficial for the university,” said Division of Administration Programs Director Ashley Majewski. “[The pilot] led us to have a better understanding of the demand for bike share on campus.”

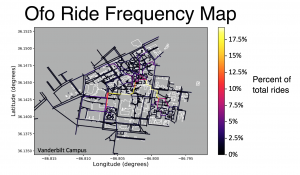

Each time an Ofo ride started, ended and at a few points in between, GPS data was collected and eventually shared with Vanderbilt, where it was analyzed in part by engineering PhD student William Barbour. The aim of this pilot was to observe where students are looking for transportation.

“[Administration] has the locations and rough geometry of every single building, every sidewalk, every stair on campus.” Barbour said. “They processed that data into basically a graph and in math terms you go from node to node, which is basically just saying we’re routing along sidewalks.”

The map, assembled by Barbour with help from administration, shows that Ofos were primarily ridden along two major paths, shown in yellow. The first path took riders between Commons and Main campus, approximately from Peabody Library to Central Library Lawn, and the second path took riders between the Athletic Area and Central Library Lawn, approximately from the Wond’ry to Stevenson Center.

“It sort of highlights the need for…this is a walkable area, but people are looking for alternative routes. And I think we’ve seen that grow as the scooters have come,” Barbour said. “Ofo has kind of served as the first hint that that was going to happen.”

Each of these two paths represented about 17.5 percent of total Ofo rides taken on campus during the pilot, meaning that approximately 45 percent of Ofo rides were taken between Highland and Main Campus or Commons and Main Campus. One of the major ride paths crosses the 21st Avenue pedestrian bridge – a bike dismount zone.

“I think some of the most interesting things we found is where people wanted to go off campus [with Ofos],” Barbour said. “There were a lot of people who wanted to take them to restaurants just off campus, to places on music row, or to the Hillsborough area. And we were surprised by the magnitude of that.”

Some students have expressed discomfort sharing narrow sidewalks with scooters travelling up to almost 15 miles per hour. Vanderbilt junior Amanda Berk said that while trying to ride over a sidewalk, her scooter fell onto her foot and caused extreme bruising that led her friends to urge her to go to the emergency room.

“It has now been around four weeks and my foot is still not fully healed which has definitely been affecting my ability to wear certain shoes, work out, and do other activities,” Berk said. “While in the ER waiting room, I talked to at least four other people there due to electric scooter accidents, including one guy who was hit by a car while on one.”

Despite her injury, Berk still strongly advocates for these devices’ presence on campus.

“I think it’s not the scooters themselves that are a safety concern, it is the reckless driving on them,” Berk said. “Without a car, having these options is super convenient and fun. I still ride the scooters, just a lot more carefully and slowly.”

Berk isn’t the only student who acknowledges the importance of safety precautions while on the scooters.

“If it’s raining, the wheels can slip out during turns and you can potentially fall,” Andrew Yancy, Vanderbilt junior, said. “But, if you’re mindful of your speed and ride in the right locations and conditions, [the scooters] can be pretty safe.”

Risks aside, the scooters have proved relatively popular among students.

“I live on Highland and I love to have the option to not have to walk everywhere,” Yancy said. “I ride the scooters whenever I can.”

Students are encouraged to report safety hazards, including scooters parked on walkways, to Vanderbilt Public Safety VUPS at (615) 322-2745.

“I once saw a bike blocking an accessible doorway and by the time I sent a message over to VUPS like five minutes later, it was already moved,” said Leigh Shoup, Chief of Staff of the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Administration.

People’s lives are at stake…parking isn’t going to save someone’s life, but the infrastructure might.

In an attempt to take into account feelings of students, administration put together a Dockless Educational and Civic Engagement Group to assist in transportation planning, made up of a handful of undergraduate and graduate students including Lanier Langdale, Vanderbilt Student Government Vice President and Campus Planning Intern.

“I do feel that our current infrastructure does not support the number of bikes and scooters we are seeing at the moment,” Langdale said. “But the university is aware of this and is actively working to improve.”

As Lime and Bird expanded to operate in over 100 cities worldwide, the companies have faced lawsuits and city-wide bans due to safety and accessibility concerns. City officials say that their infrastructure just isn’t ready for these devices.

“[Lime and Bird] are making an effort to work with cities on transportation planning, working with infrastructure – they give money straight back to the city for infrastructure improvements,” Barbour said. “People’s lives are at stake…parking isn’t going to save someone’s life, but the infrastructure might.”

All else aside, dockless transportation options shine in their potential to further sustainability efforts in replacing cars for short trips. Vanderbilt’s Ofo pilot won a Tennessee Sustainable Transportation Award from the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation.

“The city and Vanderbilt are trying to encourage more people to walk and bike and use transit; not just drive everywhere in single occupant vehicles” said Vanderbilt Executive Director of Transportation Erin Hafkenschiel, hired last month after working as director of transportation and sustainability in the Nashville Mayor’s Office.

To learn more about Vanderbilt’s mobility strategy and give input, students can attend the Mobility Expo on Tuesday, Nov. 6 at 2:00-5:30 p.m. at the Wond’ry. At 2:00 p.m., Chancellor Nicholas Zeppos along with Tennessee Department of Transportation Commissioner John Schroer will be making an announcement about a key collaboration in transportation.

“I’ve been super excited by Vanderbilt’s vision for transportation, given our location right in the middle of the city,” Hafkenschiel said. “I think there’s just a really exciting opportunity for Vanderbilt to lead the way on these conversations.”