Ok, let’s address the elephant in the room.

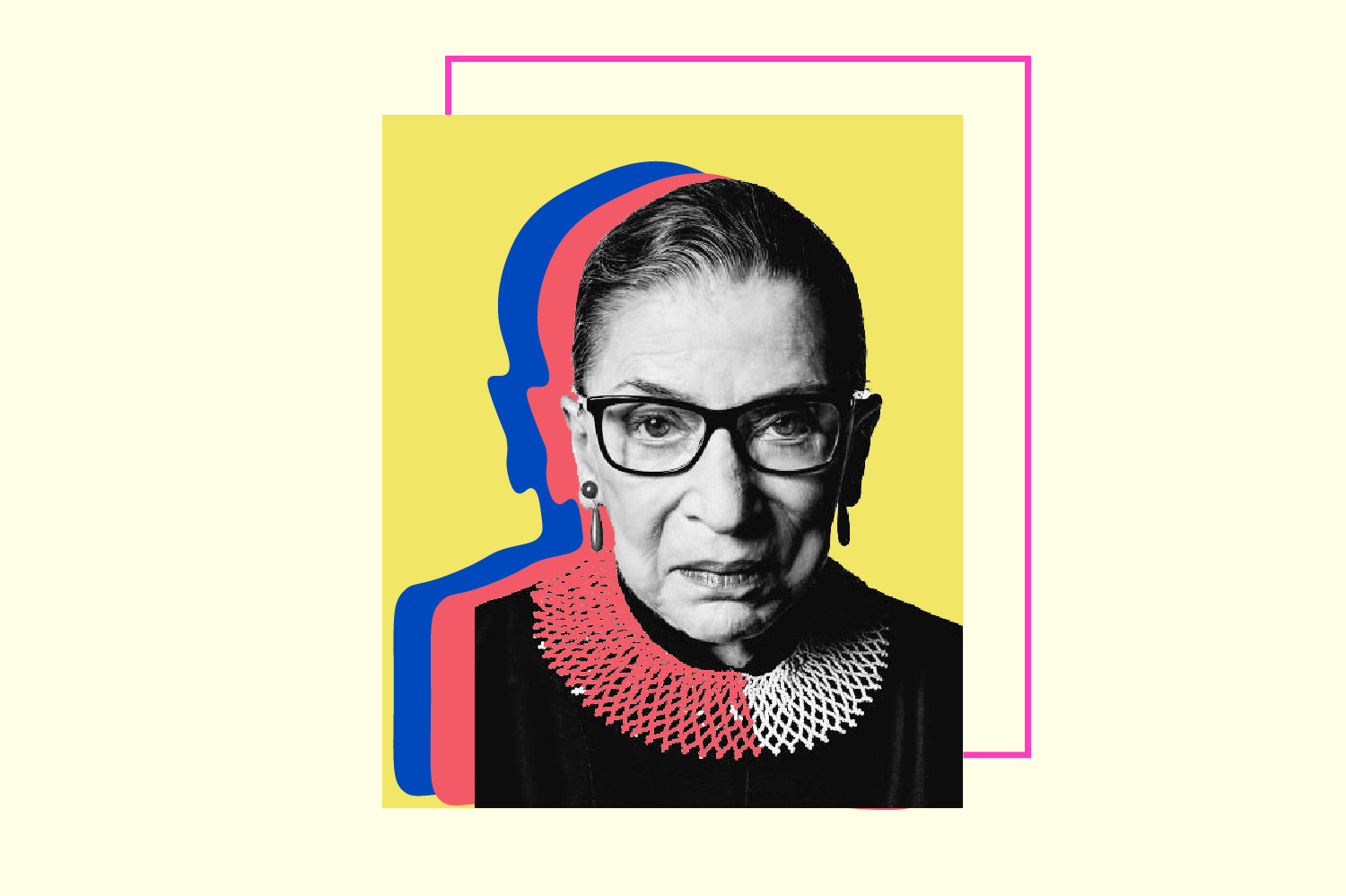

The recent passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was a shell shock for many of us—an unexpected blow to the knee. On Sept. 18, I was in the middle of a Zoom pictionary game when the notification appeared on my laptop. Upon a subtle glance at that notification, a sudden chill seeped into my spine as if all the optimism and joy in life have been wicked away. A pivotal figure who seemed undefeatable—immortal even—had vanished from the face of the earth.

Scrolling through my YouTube feed, I stumbled upon a clip of Ginsburg working out with talk show host Steven Colbert in a segment of “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.” In this hilarious segment, the sight of an elderly octogenarian donning a “Super Diva” sweatshirt whilst pumping iron was a spectacular sight to behold. Even with her thin frame and small stature, she radiates this inner strength, an immense condensation of potent determination and trailblazing prowess that was felt for over the span of six decades.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, also known as RBG or the moniker “Notorious R.B.G,” served in our nation’s forefront in women’s rights and gender discrimination reform and as an architect for equitability. Her work inside and outside of the courtroom has surmounted her as both a political and cultural icon—and rightfully so. Her fervent passion for upholding equality resonates in her powerful dissenting and majority opinions, allowing the power of words to reverberate in the chasms of change and advocacy. Her lengthy career is well-deserving of examination and can teach the young generation of Americans a thing or two.

Ginsburg was notorious for her unlikely friendship with the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Ginsburg and Scalia lie as far apart on the political spectrum as can be. Despite their obvious ideological differences over the interpretation of the Constitution, they agreed to disagree. Their relationship is a prime example of “loving the believer not the belief.” In our current ultra-partisan climate, the Herculean task of loving the believer proves to be one of the most daunting social obstacles that Americans have ever faced. Admittedly, I also find myself caught in this spiral-like paradigm. It can be a struggle on the north face of a mountain to be able to maintain an open mind, but this rare friendship proves that even in drastically polar political platforms, we can still set our differences aside and extend a laurel wreath across the aisle.

Think about it this way: the purpose of dissenting beliefs is to encourage a reexamination of ourselves through seeking the truth to the bare bones. In short, your own stance is strengthened with the critique of the opposing side. When asked if she took Scalia’s heated criticism of Ginsburg’s legal viewpoints personally, Ginsburg famously replied, “No, I take it as a challenge: How am I going to answer this in a way that is a real put-down?” The purpose of me posing this quotation is this: rather than construing opposing ideas as wrecking balls that shatter the ideas we anchor to our superficial sense of self-worth, we must view it as an opportunity to refine and polish these constructs through reason and logic.

If that belief is the essence of your entire identity in this world, then brace yourself for a rude awakening.

But by no means was Ginsburg perfect. Over the years she has accrued much criticism for not taking heed of the precedents she herself set as well as generating controversy with several unpopular perspectives. For instance, Ginsburg made her disdain for the Kaepernick protests apparent and wrote opinions that were at odds with indigenous rights and racial justice. Despite past mistakes, she made her remorse apparent (as with the case of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation, where Ginsburg appeared to be dismissive of Native American rights). Rather than allowing herself to immerse in regrets, she converted that regret into meaningful action and actively sought to seek a way to reverse her mistake—and we should take a page from that book.

Her ability to see both the good and ugly also deserves much praise, a characteristic exemplified through Roe v. Wade. Although Ginsburg supported pro-choice legislation, her criticism of Roe v. Wade was always made apparent, in that the case “seemed to have stopped the momentum on the side of change [by focusing more on the issue of privacy rather than women’s rights].” Her affinity to see the good and the bad is a phenomenon now rarely seen in our political ecosystem today, where sensitive issues are only examined on a superficial level. It is RBG’s vision that we so need to learn from. It can also be noted that Ginsburg realized that an issue like abortion cannot be diluted to a topic only pertaining to women (in fact, she has argued landmark Supreme Court cases on behalf of equal rights for men). Complex issues are complex because there is no definitive answer. There exists countless loopholes, caveats and “what ifs.” It is our duty to be able to accept the nuances of these topics; therefore, we must learn to recognize that societal issues cannot truly fit into “liberal” or “conservative” labels.

As college students, as Commodore Nation, as lifelong students and scholars and as Americans, we bear the obligation to be the bigger person by stifling the construct of cancel culture and mitigating the polarity in the community. By examining the legacy of RBG, we learn what steps we must take in order to facilitate effective civic discourse—by encouraging multidimensional analysis of topical issues and recognizing that nothing can be accomplished without compromise.

Ginsburg famously asserted, “Fight for the things that you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.”

Be the voice that unites, not divides, in honor of RBG.