I am a Vietnamese American first-year student at Vanderbilt University who, candidly, has had enough with the slipshod utterances that manage to escape the mouths of my fellow non-Black peers. “I’m from Thailand. I can say n****r. Blacks don’t have beef with me —” and so the conversation goes. The dangerous territory we enter when we sling around rhetoric like this with such clear and reckless disregard is that which welcomes the normalization of racism by tiering the different ethnic groups into various strata.

So stop saying it. It’s as easy as that. No one, irrespective of the environments in which they were raised, should be comfortable with racism. And that, my friends, is precisely what happens when someone who is not Black invites that hateful word into their lexicon: comfort in racism. “But why would anyone want to feel comfort in racism?” one might wonder. The answer, however, may perhaps be found merely by observing precedent.

It seems that many societies with multiple minority groups constantly try to make comparisons and competitive distinctions among the existing classes, elevating some while lowering others. When America saw a large influx of Asian immigrants in the earliest decades of the 20th century, there were ghettos that sprung up all across the nation that consisted of predominantly Asian-born residents. Yet when the transitional process of assimilation into American culture eventually did occur, something unique but certainly not unexpected took place. For Asian Americans (along with other minority immigrant populations), it was easy to note the obvious racial divisions that existed between whites and Blacks, and it was even easier for them to avail themselves of the low-hanging fruit by integrating themselves into the societally advantaged majority: white America. These immigrants, albeit unaccustomed to the novel and foreign traditions of the American lifestyle, were certainly not blind to the social injustices abound in America during the 1900s. In choosing to blend in with preexisting favored groups, they inadvertently deepened the divide between whites and Blacks in America.

The dangerous territory we enter when we sling around rhetoric like this with such clear and reckless disregard is that which welcomes the normalization of racism by tiering the different ethnic groups into various strata.

So now, in present-day America, it is somewhat understandable that many minority groups, whether they be Asian, Middle Eastern, Latino or otherwise, have found themselves in positions where they can choose to either hold their tongues or speak out against the microaggressive behaviors they regularly witness. These minorities exist in a sort of “ethnic middle ground” (one that is especially observable in the United States due to the dichotomous nature of American race relations). However, this does not mean they are wholly exempt from discrimination. For one, Mexican Americans have become a considerably socioeconomically disadvantaged demographic within the last few decades. Similarly, brown-skinned Americans, regardless of their countries of origin, are oftentimes shunned in social circles because of irrational and purely emotionally-driven fears of terrorism. Thus, a pattern develops in which minorities in America (really any minorities that aren’t associated with “whiteness”) are targeted and subsequently forced into a category of inferiority. All said, this is certainly not a pardon for Latino or Middle Eastern Americans to use or encourage the use of the N-word either.

So why the title of this article, then? Because Asians, at least in contemporary relations, have not been scapegoated or discriminated against nearly as readily or easily as other minority groups (let’s not forget about internment, though, America).

“Asian privilege” refers to the “[immunization] … from the systemic, routine and often lethal violence exercised by the state against the black community– not just episodes of individual killing, but the institutionalized violence of residential segregation, educational segregation, job discrimination, policing and mass incarceration.” And surely we cannot deny that Asian privilege is a hefty component to this new-wave discrimination that is taking place. Currently one of the highest-earning and most educated ethnic groups in America, Asians have consequently found that they share many (but not all) of the same privileges as their white counterparts.

So, cycling back to the crux of the argument, although from a historical standpoint “Blacks may not have much beef with you,” you should not use such rationale as an excuse to be complacent with racism. By using the N-word, especially in a manner that comes across as casual and customary, you are intentionally encouraging class stratification. At the end of the day, removing the N-word from your vocabulary is a small and painless task that will serve as just the first step of many in mending the discriminatory scars of our nation’s past.

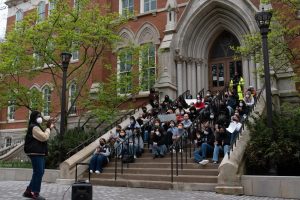

Still, to truly transcend the barriers that our ancestors created, we need to be ready to combat the stigmas that are so heavily placed on Black Americans in any form. Doing so may not necessarily feel like a prerogative to non-Black Americans, but simply because we can assume both ignorance and silence does not mean we should. Now, this is hardly meant to be seen as an attempt to weigh one marginalized group’s issues against another’s. Rather, it is a much needed intervention and invitation for all of us to recognize the plights of our peers to unite against injustice.

Where we have failed and continue to fail as a nation is in promoting amicable and beneficial coexistence among all ethnic groups. We, as non-Black, non-white Americans must help right the wrongs of the past by using our voices to take action against inaction, empowering both ourselves and those around us all the while.